Cinématographe

Camera portability made it possible to capture travel scenes and everyday life, right from the earliest days of cinema

1895

More than 120 years ago, as cameras became increasingly easy to transport and use, many inventors sought ways to create cameras that could capture movement. In 1895, the Lumière brothers invented the Cinématographe, a portable camera that could record both everyday moments and exotic travel films.

In this section, you’ll learn why the Cinématographe was considered a portable camera, who invented it and how it worked. You’ll also hear stories from camera operators of long-ago days and discover some of the films that were shot with this camera.

Refer to the Additional Resources section to see a glossary of technical terms.

A portable camera from the earliest days of cinema

It may not be as light as your smartphone camera, but back in its day, the Cinématographe was designed as a portable device. Like other photographic cameras of the late 19th century, the Cinématographe was designed to be lightweight and easy to operate, allowing filmmakers to leave the studio behind and film people living their daily lives, as well as shoot travel films all over the world.

In addition, the Cinématographe made it possible to record and project films using the same apparatus, all in the same day. Much like your smartphone, which allows you to record a video and then watch it, camera operators (then commonly called “operators”) could move around to capture “views” and then project them on a screen placed in front of viewers.

Back then, the term “views” did not mean the number of times an online video was watched. It was used to refer to movies.

A new way of seeing the world: The Lumières’ animated views

Between 1895 and 1905, the Lumière brothers created a catalogue of 1428 views shot with the Cinématographe.

Although the views seemed to have been captured on the fly, in actual fact, operators diligently prepared their shots. Images were carefully composed and the placement of the Cinématographe was meticulously selected. There was also some staging. During shoots, operators asked people not to look directly at the camera, to give the impression of true candid shots. In addition, operators sometimes orchestrated movements and changes in position so that the action always took place in front of the camera.

The desire to document daily life and discover cultures that were unfamiliar to Europeans at the time is evident in the selection of films in the catalogue.

Bains en mer filmed by Louis Lumière in 1897

© Institut Lumière

Swimmers jump into the water from a jetty; a rowboat passes by.

Bains en mer

Bains en mer was shot by Louis Lumière in France in 1897 and is one of the first vacation films in the history of cinema. Lumière, who is positioned on the shore, presents a composition incorporating three elements within the frame: the boat, the swimmers (one of them is Édouard Lumière, brother of Augustus and Louis) and the three women on the jetty (probably Joséphine, Marguerite and Rose Lumière, mother and spouses, respectively). The movement of the boat and the repeated diving of the vacationers make the scene dynamic.

Bains en mer filmed by Louis Lumière in 1897

© Institut Lumière

Swimmers jump into the water from a jetty; a rowboat passes by.

Note: The information in square brackets describes the visual content of the clip. This is a silent film.

[La Ciotat beach, Southeastern France. Daytime. Black and white.]

[A single 45-second static shot.]

[Five young swimmers wearing bathing costumes and swim caps play on and around a floating platform in the Mediterranean Sea. Some of them take turns running up to the jetty, which is on the right-hand side of the frame, and jumping back into the water. Three women are sitting at the end of the jetty, watching the children play. From the left side of the frame, in the background, a rowboat carrying two people slowly appears. Once it reaches the middle of the frame, still in the background, the occupants hoist the lateen sail. Meanwhile, the children continue to play boisterously in the water.]

[End of scene.]

Course en sacs filmed by Louis Lumière in 1896

© Institut Lumière

Young people race in gunny sacks between two rows of spectators, who are entertained by the tumbling and antics that take place during the amusing contest.

Course en sacs

Course en sacs [Sack Race] was shot in Lyon by Louis Lumière in 1896. It features Lumière factory workers taking part in a sack race, which was a very popular game at the time. The racers are surrounded on both sides by fellow workers, who came to watch the race. The protagonists are in motion, but the camera remains fixed in one spot. People enter and exit the frame, but the camera cannot follow them. Near the end of the clip, the operator’s hand appears in the frame. It motions to the spectators gathering in front of the camera to keep moving forward, so that the image remains dynamic. We can assume that the gesture was accompanied by an invective that cannot be heard, since the camera did not record sound. The operator had to remain beside the Cinématographe to continue turning the crank!

Course en sacs filmed by Louis Lumière in 1896

© Institut Lumière

Young people race in gunny sacks between two rows of spectators, who are entertained by the tumbling and antics that take place during the amusing contest.

Note: The information in square brackets describes the visual content of the clip. This is a silent film.

[A street in Lyon, France. Daytime. Black and white.]

[A single 38-second static shot.]

[In the background, several men are lined up across the width of the street. Each participant has placed both of his legs inside a large jute bag that is tied at his waist. The participants must therefore hop to the finish line, which is outside of the frame. The race begins when the referee waves a flag. People are lined up along both sides of the street to cheer them on.

A second round of participants begins to race, and the spectators follow them. Men, women and children are now walking in the street.

The last participant in the race is struggling to move forward. One of the spectators gives him an encouraging pat on the back, which causes him to fall down. He gets back up and continues the race with difficulty, but with a smile on his face, until he exits the frame.

The spectators gather in front of the camera and many people stare at it. The camera operator’s arm enters the frame and signals to the spectators to keep moving forward.]

[End of scene.]

Examples of films showing everyday life:

Photogram from view no 88, Repas de bébé, filmed by Louis Lumière in 1895.

Public domain

Repas de bébé is an example of a film showing everyday life. It was one of the first home movies ever made. Auguste Lumière, sitting on the left, feeds his daughter Andrée. His wife Marguerite is on the right-hand side of the frame.

Photogram from view vue no 653, Arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat, filmed by Louis Lumière in 1897.

Public domain

Arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat is another view of everyday life. The framing of this view highlights the movement of the train, which was a symbol of speed and modern technology.

Examples of travel films:

These views, which were filmed around the world, provided glimpses of countries and cultures unfamiliar to European viewers.

Porte de Jaffa : côté est filmed by Alexandre Promio in 1897

Public domain

Pedestrian traffic in a street in Jerusalem.

Porte de Jaffa : côté est

Alexander Promio, a Lumière operator, filmed Porte de Jaffa : côté est in 1897, right in the middle of a street in Jerusalem. Some passersby look directly at the camera and seem intrigued by the operator, who is turning the crank. People enter and exit the frame without the camera following them; it is fixed in place. The shops on the left and the wall on the right form convergence lines that lead the viewer’s gaze to the background and the subject of this view: the Jaffa Gate.

Porte de Jaffa : côté est filmed by Alexandre Promio in 1897

Public domain

Pedestrian traffic in a street in Jerusalem.

Note: The information in square brackets describes the visual content of the video. This is a silent film.

[Street scene in front of the Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem, Near East. Daytime. Black and white.]

[A single 40-second static shot.]

[A passerby is intrigued by the camera and approaches it until only his head and shoulders are in the frame.

He becomes slightly blurred and then partially exits to the right of the frame. He then furtively passes back in front of the camera, from right to left, before exiting the field of view. We then see pedestrians walking in the street. Some stroll leisurely while others, carrying various objects, move more quickly. Two youths in the background stand out from the crowd, on the right side of the image. They sway their upper bodies quickly from side to side, probably to get the camera operator’s attention. On the left, there is a row of small shops. On the right edge of the frame are other storefronts, as well as the city walls. In the background is the Jaffa Gate, leading to Old Jerusalem. It is composed of large cut stones, a pointed supporting arch over the entrance, loopholes and battlements.]

[End of scene.]

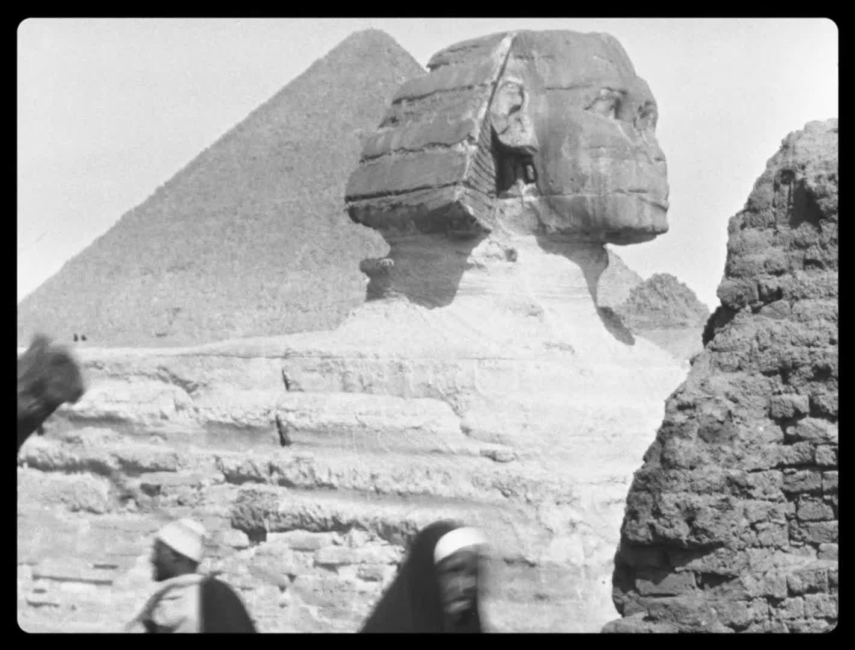

Photogram from view no 381, Les pyramides (vue générale), filmed by Alexandre Promio in 1897.

Public domain

This view, which was shot in Egypt, features the Sphinx and the Pyramid of Cheops, which is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. A caravan of camel drivers passes by in the foreground, speaking to the authenticity of this faraway land.

The origins of an invention

In the late 19th century, many inventors were searching for ways to record motion. The idea of photographing bursts of still images and projecting them sequentially was meant to give the brain the illusion that the static images were in motion.

Flip book entitled Gamineries, 1967. It consists of images from Émile Cohl’s film.

© Christoph Benjamin Schulz

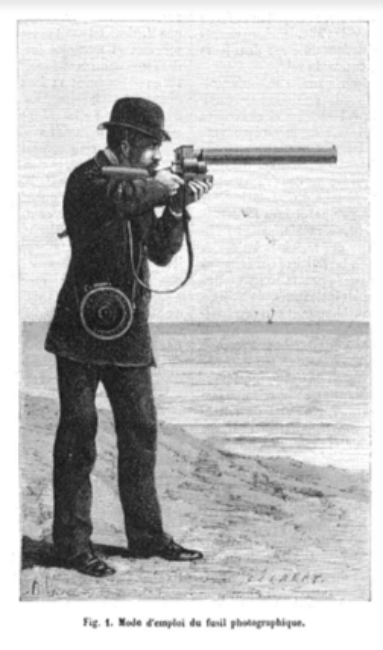

A few years before the invention of the Cinématographe, Étienne-Jules Marey invented portable devices capable of reproducing movement, such as the chronophotograph and the chronophotographic gun.

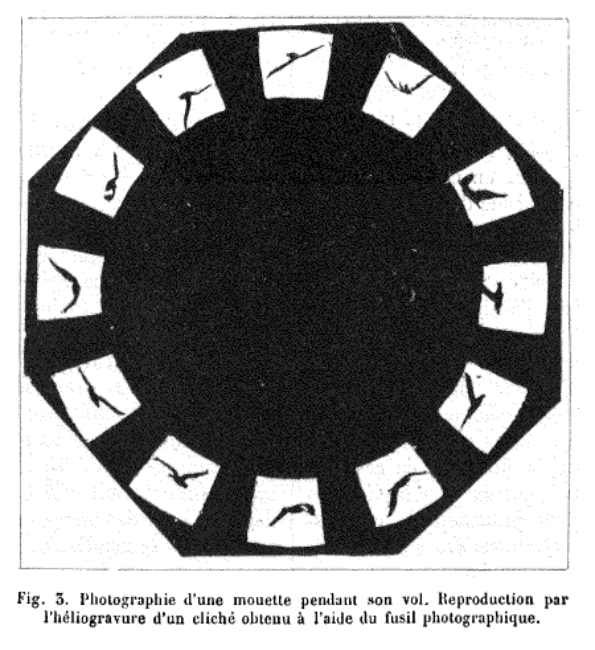

Engraving of the chronophotographic gun designed by Étienne-Jules Marey, as published in La Nature, 1888, p. 328.

Domaine public

Marey, Etienne-Jules. 1882. “Le fusil photographique.” La Nature : revue des sciences, vol. 18, no. 464: 326-330. Image obtained using the chronophotographic gun, showing twelve shots of a gull in flight.

Public domain

These twelve images were photographed in one second. For each image, the exposure time was 1/720 of a second.

Chronophotograph on fixed plate by Étienne-Jules Marey, negative, 1886. The image creates the illusion of movement by superimposing twelve shots that were captured in one second.

Public domain

The purpose of chronophotography was primarily scientific; the objective was to take multiple photographs in order to analyze the different positions of bodies in motion.

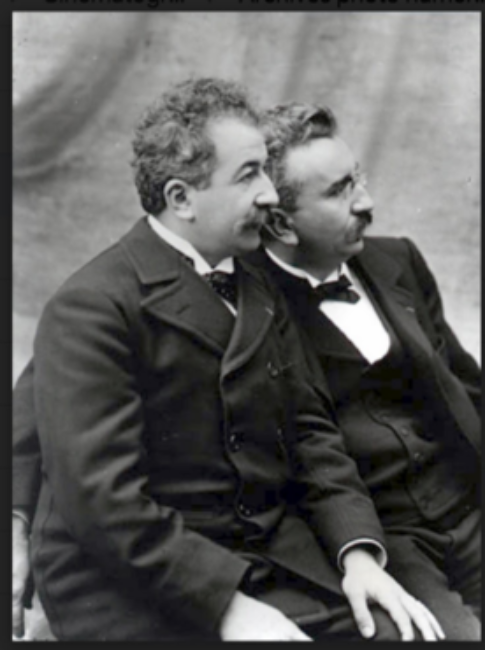

The Cinématographe was invented by brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière. Both were entrepreneurs, engineers and inventors. Auguste and Louis began their careers in Lyon in 1884 as partners of their father, photographer Antoine Lumière, in the Société Anonyme des Plaques et Papiers Photographiques Antoine Lumière et ses fils. Between the two brothers, they filed nearly 340 patents over the course of their careers. Revenue from their patents and from the sale of photographic plates provided them with the financial means to develop the Cinématographe.

Photograph of Auguste Lumière (1862-1954) and Louis Lumière (1864-1948).

Public domain

In the introduction to the Cinématographe patent, the Lumière brothers explained their intent to design a self-contained machine that would be light, portable and easy to operate. Operators could be amateurs with a basic knowledge of photography, who would be able to move around to capture views and then project them, all on their own.

Lumière, A., and L. Lumière. 1895. Brevet d’invention de 15 ans pour un appareil servant à l’obtention et à la vision des épreuves chronophotographique [Fifteen-year patent for an apparatus to film and view chronophotographic proofs]. No. 245032. Lyon, France. 11 p.

pdf (2.01 MB)Patent of invention for the Cinématographe

This eleven-page handwritten patent contains two illustrations of the future device. It protects the intellectual property of the inventors and guarantees the inventors’ exclusive rights to the patented invention.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Lumière, A., and L. Lumière. 1895. Brevet d’invention de 15 ans pour un appareil servant à l’obtention et à la vision des épreuves chronophotographique [Fifteen-year patent for an apparatus to film and view chronophotographic proofs]. No. 245032. Lyon, France. 11 p.

pdf (2.01 MB)Summary of the 11-page handwritten patent:

The patent explains the Lumière brothers’ intention to build a reversible device that would be used to both capture and view images.

Translation of page one of the patent:

Lépinette and Rabilloud French and Foreign Patent Office in Lyon.

Fifteen-year patent for an apparatus to film and view chronophotographic proofs.

Requested by Mr. Auguste Lumière and Mr. Louis Lumière.

Specification.

We know that chronophotographic proofs provide the illusion of

movement through the rapid succession of (…)

Today, we can capture videos on our smartphones, anytime, using just our fingertips, thanks to camera inventors who searched for ways to record movement!

A non-portable device from the same era: The Kinetograph

To better understand why the Lumière brothers’ Cinématographe was considered portable and how it allowed operators to work alone, let’s compare it to a camera that was invented by Thomas Edison at around the same time: the Kinetograph.

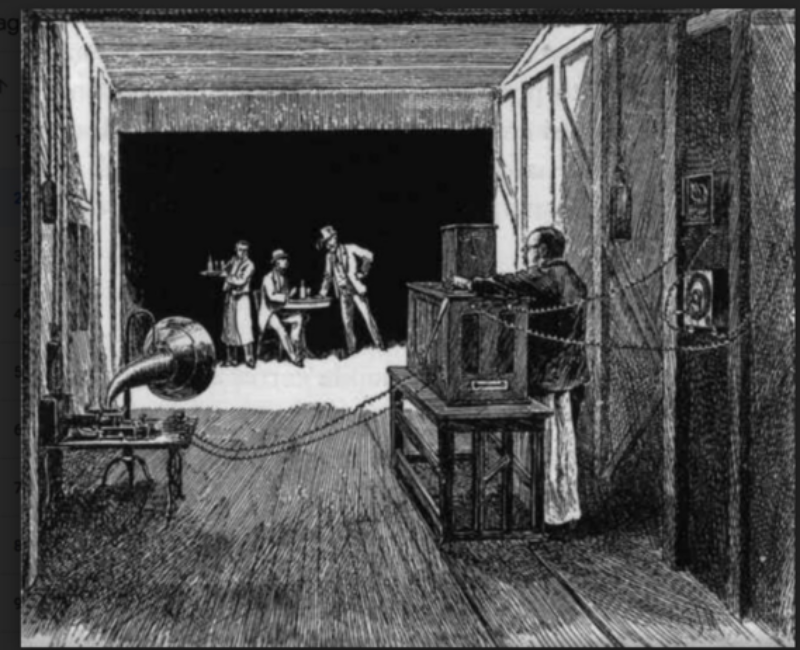

In 1891, a few years before the Cinématographe was invented, Edison developed the Kinetograph, which he used in his studio called the Kinetographic Theater (nicknamed the Black Maria). The Black Maria made it possible to control light levels, thus meeting Edison’s requirements for indoor shoots, which included circus acts and vaudeville performances.

In West Orange, New Jersey, just across from Manhattan, Thomas Edison built the world’s first film studio, called the Kinetographic Theater. It was a lightweight building constructed entirely of tar paper. The interior was painted black, and on sunny days, it was stifling hot. Laurie Dickson […] called it the Black Maria—the slang name given to the paddy wagons of American police forces—which said a lot about how uncomfortable it was. The roof was retractable to let in the much-needed daylight, and as the sun moved across the sky, a central rotating platform and circular track repositioned the small building. [Translation]

(Briselance and Morin 2010, 25).

The Kinetograph was situated inside Edison’s studio and ran on electricity. It could not be moved.

Drawing by E.J. Meeker of a film being shot inside Edison’s studio, 1894.

Public domain

An 1894 photograph of the world’s first movie studio, the Kinetographic Theater, also known as the Black Maria, designed by Thomas Edison in New Jersey in 1892.

Public domain

By comparing the dimensions of the Cinématographe and the Kinetograph, we quickly understand that their inventors had two completely different visions of what films and film shoots should be. The Lumière brothers’ Cinématographe made it possible to change locations to capture people’s everyday lives and make travel films, whereas the Kinetograph made it possible to film performances indoors in a controlled environment.

Cinématographe technical data sheet

Which of this device’s features made it portable and easy to use and allowed it to get close to its subjects?

Specifications

- Measurements

- 22.5 cm x 19 cm x 28 cm It was relatively small and easy to handle.

- Materials

- Wood, metal, leather and fibres.

- Weight

- 4.3 kg, including the projection lens and unloaded magazine (no film) The body of the camera was relatively light.

- Frame rate

- Approximately 16 frames per second (fps). The speed could be varied because the film was advanced by a crank handle powered by the operator. Hence the importance of maintaining a constant speed.

Components and accessories

- Main unit

- Wooden box.

- Magazine

- A lightproof wooden box to protect the blank film.

- Take-up magazine

- A metal box inside the main wooden box containing the exposed film (on which the images were printed).

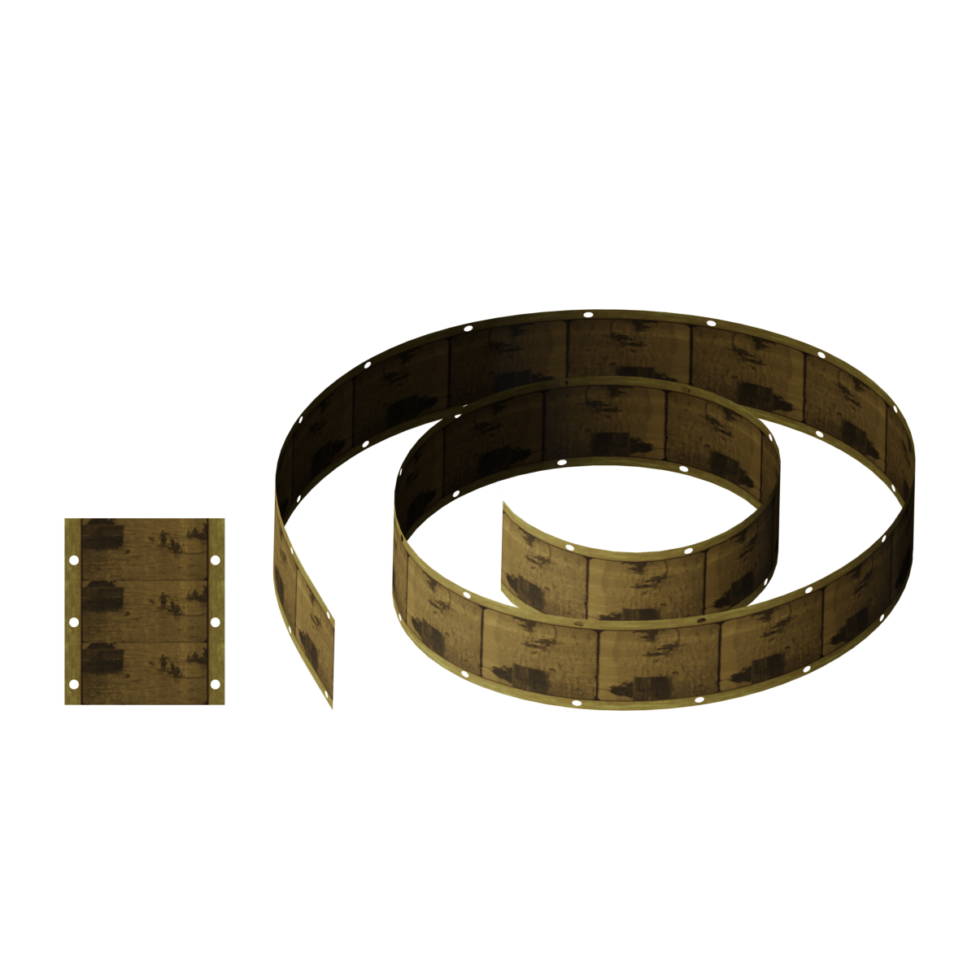

- Film

- A 17-metre strip lasting about 50 seconds.

- Crank handle

- For advancing the film inside the housing. To keep a steady pace, operators often sang “Sambre et Meuse.”

- Taking lens

- Equipped with a lens that reproduced the approximate angle and perspective of the human eye.

- Projection lens

- A lens with a long focal length. Presumably, this allowed the camera to be concealed at the back of the room.

- Tripod

- The Cinématographe was set on a tripod to allow operators to hold the camera firmly with their left hand while operating the crank with their right.

Features

- Triple-function

- The camera could record, develop and project images.

- Flexible film

- While glass plates continued to be used for still photography, the Lumière brothers used film that was flexible and transparent.

- No viewfinder

- A viewfinder is a small window through which the operator can see the image that will be shot. The Cinématographe was not equipped with one.

- No microphone

- The Cinématographe could not record sound. All films shot with this camera were silent.

Operation and handling

You’ve probably never read an instruction manual for your smartphone camera, have you? The Cinématographe may not have been as intuitive to use as your phone camera, but with some basic photography knowledge, along with the Lumière brothers’ instruction manual, an amateur photographer could operate it.

The following excerpt from a letter written by Louis Lumière illustrates his desire to design a device that could be used by a single operator.

From Louis Lumière to H. Mesnier on October 22, 1895,

Mr. H. Mesnier, Bordeaux

We are in possession of your correspondence dated the 20th of this month and have read its contents. We have not forgotten your previous request concerning our Cinématographe, but we are not yet certain of the price of this apparatus, nor of the timing of its sale. As soon as we can inform you, we will do so.

Our simple device will be easy to use and is unlikely to be damaged if placed in the right hands.

There will be no need for special knowledge when handling this device. A basic knowledge of photography will suffice.

Our device has an advantage over Edison’s (1) in that for public presentations, the projected images may be viewed by a very large number of spectators at once, which is not the case with the Kinetoscope (2).

Yours sincerely,

L. Lumière.

Note 1: Before inventing his famous phonograph in 1878, Edison improved the printing telegraph system and invented an automatic telegraph that used perforated tape. Considered the father of moving pictures in the United States, he became interested in this subject following a lecture given by Muybridge. He wished to reproduce not only movement, but also the sound that accompanied it. Edison’s genius allowed him to not only invent and perfect numerous systems, but also to surround himself with a highly qualified team. To ensure images were equidistant, they used Eastman’s celluloid film, which at first was notched (1888) and later perforated (1889). From 1890-1891, they developed the Kinetograph, which was the first real movie camera. Surprisingly, however, Edison did not see a future for the projector. In an individual apparatus, the spectator viewed the synthesis of movement: when the Kinetoscope arrived in France in 1894, the Bulletin de la Société française de Photographie wrote, “Ce n’est qu’un jouet de haute valeur [It is nothing but an expensive toy].” The Kinetoscope must of course be included among the many elements that Louis Lumière drew upon to create the Lumière Cinématographe.

Note 2: It weighs less than 5 kilograms and is easier to handle than its main competitor the Kinetograph, whose greater weight and volume make handling it much more awkward, especially for reporting. Moreover, images from the Kinetoscope can only be seen by one viewer at a time through an eyepiece in a box. Contrary to public screenings, in dark rooms, on a large screen, much more similar to what we call cinema today.”

Lumière, A., and L. Lumière. 1994. Correspondances 1890-1953. Paris: Cahiers du cinéma. [Translation]

In the Lumière brothers’ 30-page instruction manual, operators could find detailed explanations of the camera’s functions and the preparations to be made before shooting.

Lumière, A. and L. Lumière. 1897. “Le Cinématographe Par MM. Auguste Et Louis Lumière.” La Revue Du Siècle, no. 120: 233-63.

pdf (5.59 MB)La revue du siècle, Mai-juin 1897

In its May-June 1897 issue, La Revue du siècle : littéraire, artistique et scientifique illustrée published the complete Cinématographe instruction manual so that new owners would have a user manual to follow.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Lumière, A. and L. Lumière. 1897. “Le Cinématographe Par MM. Auguste Et Louis Lumière.” La Revue Du Siècle, no. 120: 233-63.

pdf (5.59 MB)This is an excerpt from La Revue du siècle, which published the 30-page Cinématographe instruction manual in May-June 1897. The general principles of the device are explained, and each step is described and illustrated with drawings by Poyet. The six sections are: Principles of the Cinématographe; Description of the camera; Obtaining negatives; Development, washing and fixing; Obtaining positives; and Projection.

So, how was the Cinématographe operated?

The operator’s first step was to set up the Cinématographe on its tripod. Next, the image had to be framed and focused. Like photo cameras of the time, the Cinématographe did not have a viewfinder (a small window through which the operator could see the image being shot). The operator had to plan the frame before shooting because once the camera started rolling, it was not possible to see what was being filmed.

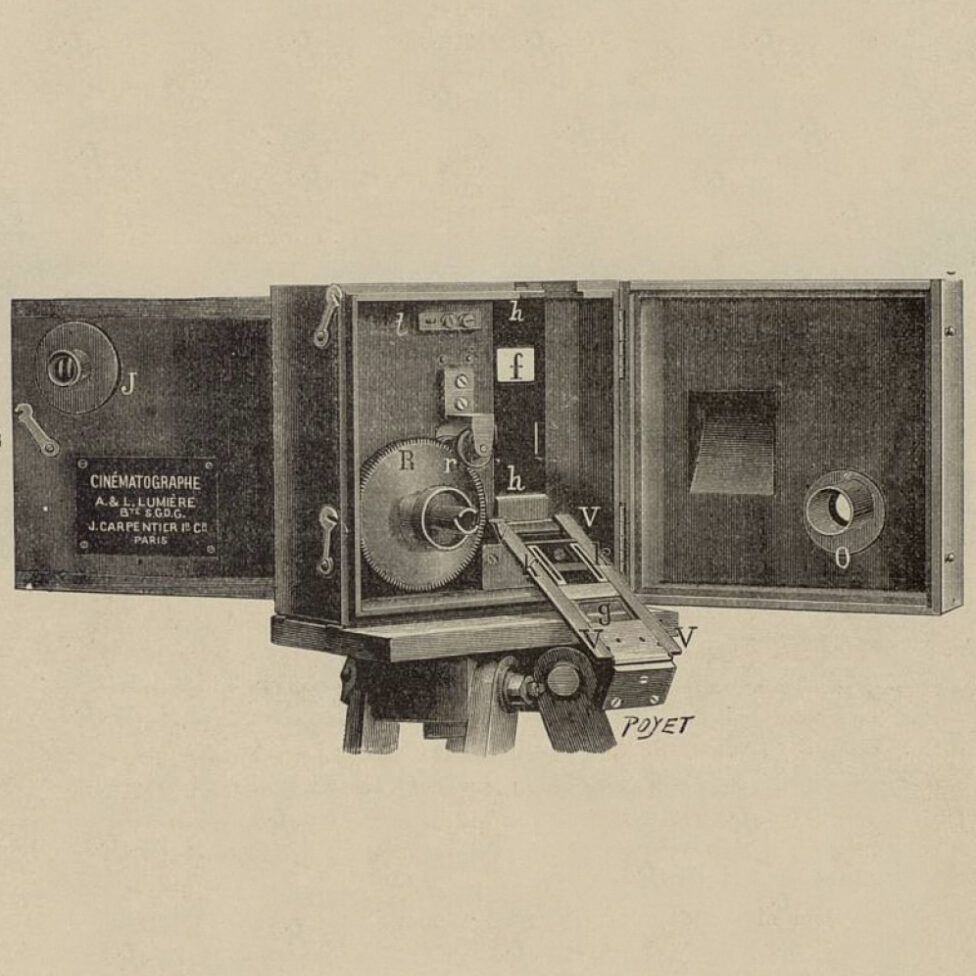

Illustration by Louis Poyet in the instruction manual, showing the interior of Cinématographe in open position. It shows the position of the film as it advances through the drive mechanism before the camera is closed for shooting. In order to make the drawing easier to understand, the take-up magazine enclosing the exposed film was not included. Framing and focusing were done with the camera open.

Public domain

As with a photographic chamber, the operator framed before loading the film with the camera open, through the camera gate and the lens, using a polished surface on which the image appeared. The film was then put in place, the machine was closed, the crank was inserted, and shooting could begin whenever one wished. All these operations, including the shooting, were technically ‘blind’: the camera operator, beside his machine, could control what was in the frame only by guesswork. [Translation]

(Turquety 2014, 83).

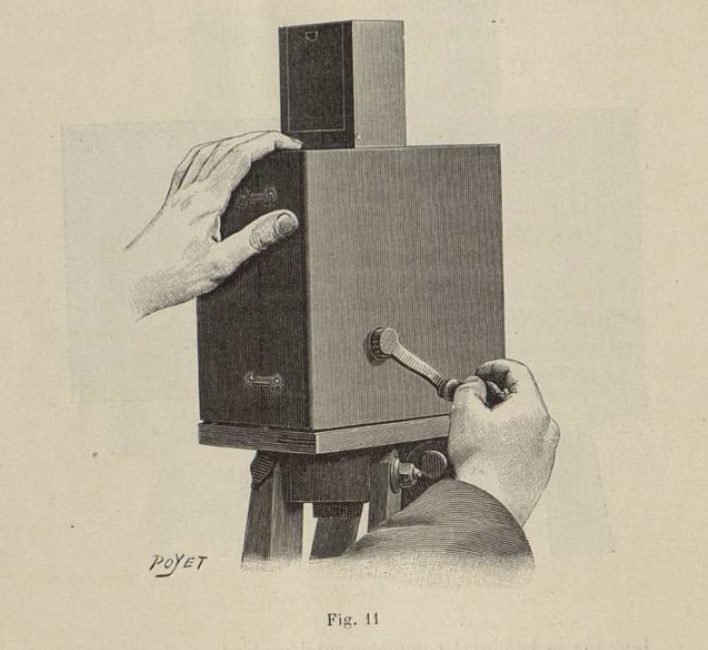

When operators were ready to start filming, they turned the crank with their right hands. The crank had to be turned at a rate of two revolutions per second to advance the film past the print window at a speed that would record about 16 frames per second. Beginner operators often hummed certain songs to maintain a steady pace. Because the body of the camera was relatively light, operators used their left hands to hold it firmly in place and keep it as stable as possible. They therefore had to remain next to the camera while shooting.

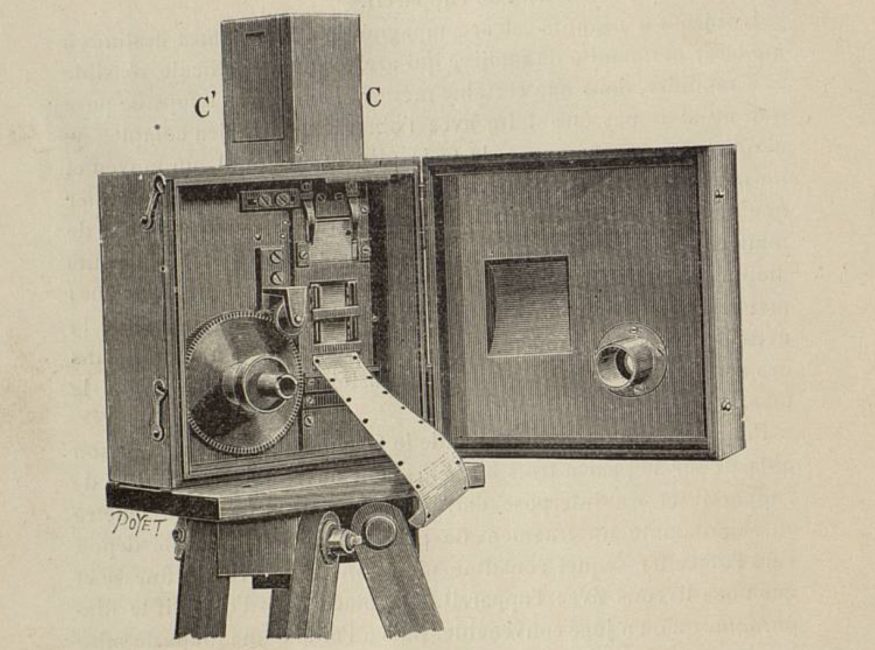

Illustration by Louis Poyet in the instruction manual, showing the positions of the operator’s hands while filming. The left hand holds the device firmly while the right hand operates the crank.

Copyright: Public domain

To capture everything they wished to record on the 17 metres of film available in the camera—that is, about 50 seconds’ worth—operators had to meticulously prepare their shots.

The Cinématographe operator: A one-person team

So, who had the pleasure and privilege of operating the Cinématographe?

In 1896, a few months after the first public paid film screening in Paris, the Lumière company trained operators to go out on location, all around the globe, and create a “catalogue of views,” that is, a collection of short films. During the first year, these operators were the only people to use the device.

In May 1897, the device was made available for sale. Between 400 and 500 Cinématographe cameras were produced and used, mostly by people who wished to pursue the occupation professionally. The Lumière brothers primarily wished to appeal to professionals, as well as to amateur photographers who had a good knowledge of photography and were already customers of theirs. However, the camera was not within everyone’s financial reach, nor was film. With all of its accessories, the Cinématographe cost 1,650 former francs, or about $10,000 CAD.

Amateur filmmakers and professional operators hired by the Lumière brothers developed a unique relationship with this camera that provided them with so much freedom to move around. Cinématographe operators could transport the camera around the world and then record, develop and project their films, all in one day. In a manner of speaking, the operator was a one-person team.

Photograph of Alexandre Promio immortalizing a wedding in front of the Lumière villa, n.d.

© Institut Lumière

In his memoirs, Félix Mesguich, an operator employed by the Lumière company, recounted his multiple trips around the world, attesting to the freedom enjoyed by Cinématographe operators of the time, who could film while travelling.

Ah! When we set out for an isolated and distant corner of our planet, we didn’t bother with a retinue. It was not an expedition. No help was needed, other than a few hirelings recruited on the spot when conditions were difficult. I recall roaming through mountains and valleys, in unfamiliar countries, heavily laden with my tripod and this magic reel with which I recorded the world and stored it on film.

Alone! Yes, I was alone, or almost! I had to think of everything, prepare the itinerary, find lodging, transport the accessories, find the subjects, take the shots, develop the negatives, fix the positives, and often even project them [Translation]

(Félix Mesguich, Lumière operator, 1933, xii).

Mesguich, Félix. 1933. Tours de manivelle : souvenirs d’un chasseur d’images. Paris : Grasset.

(Archive from which the above quote is extracted)

Tours de manivelle : souvenirs d’un chasseur d’images

Lumière operator Félix Mesguich wrote his memoirs in a book more than 300 pages long, recounting his multiple trips and some of the challenges he encountered while working as an operator for the Lumière company.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Mesguich, Félix. 1933. Tours de manivelle : souvenirs d’un chasseur d’images. Paris : Grasset.

(Archive from which the above quote is extracted)

This archival document contains the four-page foreword from Mesguich’s book. It summarizes his career as an operator and details the adventures he experienced while living that exciting life.

The following is a translation of the four-page foreword:

Foreword

We sometimes speak of vocations. It was chance that led me to mine, the chance of a family relationship, along with the coincidental timing of my discharge from military service at exact moment that the Lumière brothers’ invention, which had been finalized in late 1895, was beginning to gain momentum, slowly at first, but unstoppably.

To have been one of the modest artisans at a time when no one could have foreseen such magnitude, to have been the attentive pupil of the inventors and to have devoted myself with heart and soul to my chosen profession, gives me some pride.

It was thus by chance that I was thrust into a cinematographic career.

Some prepare their paths from childhood. For me, nothing from my youth could have determined my destiny because cinema was unknown at that time. Such an ambition could not have come from the Magic Lantern of our forefathers, the original concept of projection. At the time, one could hardly imagine that, thanks to the Lumière brothers’ discovery, it would become dynamic and acquire the condition indispensable to all life: movement.

In considering my voyage through this vast universe, restless yet rich in visions and dreams, I believe that, from the very beginning, it was not only images that cinema put into motion, but also the operators responsible for supplying them.

Of these, I was one of the first.

When I see how the image hunter’s mission has been transformed, I cannot help but reflect on the past. The speed of communication has shrunk the universe, and while I admire the importance of the means available to my successors today, I also think, without any bitterness, and even with some pleasure, and perhaps with some pride, of my former life.

Ah! When we set out for an isolated and distant corner of our planet, we didn’t bother with a retinue. It was not an expedition. No help was needed, other than a few hirelings recruited on the spot when conditions were difficult. I recall roaming through mountains and valleys, in unfamiliar countries, heavily laden with my tripod and this magic reel with which I captured the world and stored it on film.

Alone! Yes, I was alone, or almost! I had to think of everything, prepare the itinerary, find lodging, transport the accessories, find the subjects, take the shots, develop the negatives, fix the positives, and often even project them.

A little-known era, a heroic time, which I cannot recollect without feeling moved.

I was young, and I had faith!

And while occasionally, in years that offered their share of hardships, I was sometimes seized, perhaps not with doubt, but with some concern about the future of this new art form to which I was attached, it was only fleeting.

I set out again with even greater ardour.

I crossed all the seas, and, like the Wandering Jew, walked without pausing over all the continents, but whereas the latter kept for himself, as fodder for his inner dream, visions of the ever-changing spectacles the universe dispensed to him, my ambition was to capture them in my image box so that other men, my brothers, could experience all their beauty and share my emotions.

As a tireless traveler, I have beheld the most beautiful landscapes, I have contemplated the most representative vestiges of ancient civilizations. Poets and writers have written volumes about them.

My task was limited by the lens. It consisted simply in capturing the fleeting aspects of the world, as my camera—at sixteen images per second—recorded them during my wanderings.

While attempting to reconstruct this past, I do not pretend to be ignorant of the challenges of the task; the crank has always been more familiar to me than the pen, and I believe it would be easier for me to take another trip around the world than to describe the zigzags of my travels. Perhaps I will be unable to relate the episodes with their original liveliness, with the astonishment, enthusiasm and excitement I experienced, but I am tempted to try.

While recently reading The History of the Cinématographe, a highly researched work by my friend Michel Coissac, I was drawn to this passage: “When, comfortably seated in a chair, the spectator sees on the screen the varied scenes that bold and courageous operators have ventured to fix on film in the jungle, in the bush or in the icy solitudes of the polar regions, does he take the trouble to reflect on all the patience and endurance it took to successfully carry out this work, and those who frequent the cinema theatres will not be the only ones to be surprised by the dangers certain shots command.”

I wish to try to show them.

Passion for this occupation drives one to daring recklessness of which it would be vain to be proud, because at the time one is unaware of it. Later, when one “realizes” them, the risks become apparent.

But by transporting my readers thirty-seven years back in time, my sole intention is not to associate them with my joys or misfortunes, nor with the perils I faced and from which salvation sometimes came only from a little luck. I would simply like to evoke for them scenes touching on history or rich in the kind of originality which the progress of civilization destroys a little more each day.

But, as I reflect upon a long career, I sometimes ask myself, “Has my task been useful, at least?” In good conscience, it seems to me today that I am able to answer affirmatively, since I have been given the opportunity to reveal to an entire generation, in visual form, the landscapes of our planet and the customs of its most distant inhabitants, in their true reality, which no one had yet done.

Those who read me to the end will discover the many films of today for which mine have been the precursors.

It is not without emotion that I examine the long string of memories of my vagabond life. I have found postcards sent to my family, documents collected on site, letters from ambassadors abroad, my old military booklet with its pages covered with multiple consular stamps, and also some travel logbooks, alas! quite incomplete.

These yellowed pages will help me to assemble these first cinematographic reports, which I wish to link together in a brief but faithful narrative. [Translation]

Additional information

This motion picture glossary will help you better understand some of the terminology used.

Are you the inquisitive type? Would you like to learn more about the Lumière Cinématographe? The following websites will provide you with additional information.

- Video on the story of the Lumière brothers

- Trailer for the film Lumière ! L’aventure commence

- Account by Alexandre Promio, Lumière operator (in French only)

- The cinematographic work of the Lumière brothers, sorted by shooting location

- The first paid public screening in Paris

- Sambre et Meuse, one of the songs sung by the first operators of the time

- The history of Cinématographe No. 16 from the collections of the Cinémathèque québécoise

Bibliography

Briselance, Marie-France et Jean-Claude Morin. 2010. Grammaire du cinéma. Paris : Nouveau Monde.

Coissac, Georges-Michel. 1925. Histoire du cinématographe de ses origines à nos jours. Paris : Éditions du « Cinéopse ».

Lumière, Auguste et Louis Lumière. 1895. Brevet d’invention de 15 ans pour un appareil servant à l’obtention et à la vision des épreuves chronophotographique. No. 245032. Lyon, France. 11 p.

Lumière, Auguste et Louis Lumière. 1897. « Le cinématographe par MM. Auguste et Louis Lumière ». La revue du siècle, no. 120, p. 233-263.

Lumière, Auguste et Louis Lumière. 1994. Correspondances 1890-1953. Paris : Cahiers du cinéma.

Mesguich, Félix. 1933. Tours de manivelle : souvenirs d’un chasseur d’images. Paris : Grasset.

Turquety, Benoît. 2019. Inventing Cinema. Machines, Gestures and Media History. Amsterdam : Amsterdam University Press.

Rittaud-Hutinet. 1985. Le cinéma des origines : les frères Lumière et leurs opérateurs. Seyssel : Champ Vallon.

Want to find out more?

Take an audio journey into the world of this device.