The small, clever, lightweight Bolex H16 allows amateur filmmakers to experiment with special effects at the time of shooting. It can be operated by solo filmmakers and it provides significant creative freedom to professionals and amateurs alike.

Refer to the “Additional Resources” section to see a glossary of technical terms.

The Bolex H16 and film portraiture

The Bolex H16 is an excellent choice for experimenting with film portraiture. It was designed to be both smart and easy to handle. Thanks to its precision mechanisms, this camera makes it possible to experiment with various effects at the time of shooting, such as overlays, dissolves, etc. This sturdy, stable, Swiss-made camera can be used for a wide range of purposes, from simple filming to artistic creation. Its technical ease of use permits great spontaneity during shoots.

Its functions can be accessed by amateurs with solid basic photography skills and by professionals, whether or not they are working alone. In addition to being lightweight, the Bolex is equipped with a viewfinder and can be carried in one hand.

This camera is especially popular with amateur and experimental filmmakers for portrait work: self-portraits, family portraits and group portraits. The Bolex serves as an extension of their eyes and body.

A few films shot with the Bolex

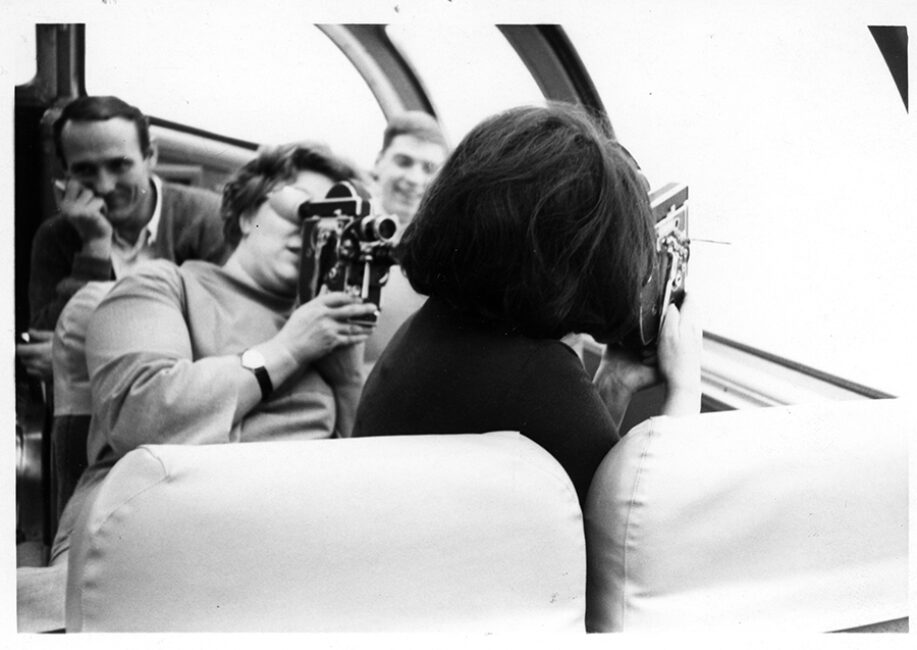

A and B in Ontario, produced by Joyce Wieland and Hollis Frampton, 1967

Cinémathèque québécoise collections

A and B in Ontario was completed eighteen years after the original material was shot. After Frampton’s death, the film was edited by Wieland, who created a cinematic dialogue in which the collaborators filmed each other with their cameras (in the spirit of the 1960s). (Lightcone.org)

A and B in Ontario

In this clip from A and B in Ontario, producer Joyce Wieland and her associate Hollis Frampton play hide-and-seek with their respective Bolexes. Each of them films the other’s camera. The cameras imitate the occasionally halting movements of their bodies, serving as extensions of their eyes and arms. Even better, Wieland’s camera, equipped with a zoom lens, allows her to capture close-up shots of her friend while maintaining her distance.

A and B in Ontario, produced by Joyce Wieland and Hollis Frampton, 1967

Cinémathèque québécoise collections

A and B in Ontario was completed eighteen years after the original material was shot. After Frampton’s death, the film was edited by Wieland, who created a cinematic dialogue in which the collaborators filmed each other with their cameras (in the spirit of the 1960s). (Lightcone.org)

Note: The information in square brackets describes the audio and visual content of the clip. There is no dialogue in this film.

[0:56 second excerpt.]

[Outdoors, Ontario, a commercial street in summer. Black and white.] [This sequence is an alternating montage of subjective shots of the two characters. A game of camera versus camera, or of hide-and-seek. It moves quickly. Joyce Wieland shoots with Camera A, which has a zoom lens, and Hollis Frampton shoots with Camera B, which does not.] [The muffled sound of the rolling camera can be heard throughout the clip.]

[Camera A: Zoom in on Frampton, finishing with a chest shot. With his eye on the viewfinder, Frampton points camera B toward Wieland. Wieland obstructs the left-hand side of the image by hiding behind a post, so that she cannot be filmed. The frame is divided in two, with a black screen on the left and Frampton and other passers-by, facing the camera, on the right. The post behind which Wieland hides ends up creating the black screen, like a sort of transition shot.]

[Camera B: Reverse angle. Full shot of Wieland. Sidestepping to the right of the frame, she hides behind a post, holding camera A. She allows her camera to peek out slightly from behind the post. A passerby from the previous shot re-enters the frame on the left, this time viewed from behind.] [The sound of a camera’s motor being wound up.]

[Camera A: Close-up of Frampton’s torso and his camera, which he holds on its side. Turning a crank on one side of the camera, he winds up the spring-operated mechanism. Zoom out to fit Frampton’s face into the frame. He escapes to the left. A truck drives by on the road and Wieland tracks it to the right with her camera.]

[Camera A: Close-up, unfocused, side-to-side shot of advertising posters on a post. Frampton appears very briefly on the left.]

[Camera B: Reverse angle. Full shot of Wieland, who is filming straight ahead of her. On the left are the advertising posters from the previous image. There is great depth of field in this shot, revealing the pavement of the sidewalk, the shadows of the buildings and the passers-by. Frampton hides behind the advertising poster-covered post, on the left, which blocks the field of view and hides Wieland.]

[Camera A: Close-up of Frampton filming Wieland. He has one hand on the camera’s handle, one hand on the top of the camera, and his eye on the viewfinder. He occupies the entire right half of the frame. In the background, the street and a storefront are visible. He exits the frame to the right. Wieland swivels to the right to follow him, but only manages to catch a close-up of his camera, and then a parked car].

[Camera B: Reverse angle. Frampton moves around the advertising poster-covered post to chase Wieland, who aims her camera at him.]

[Black]

[Camera A: Frampton, hidden behind a fence, holds his Bolex over his head at arm’s length, one hand on the handle and the other on the top of the camera. He moves toward the left.]

[Camera B: Reverse angle. Long shot of the backs of buildings, in an alleyway. The sunlight creates a bright glare on the image, twice. Wieland is standing on a stairway. In the background are brick walls, doors and windows. The image jumps around. Frampton travels from left to right without looking at what he is filming.]

[Camera A: Continuing shot of Frampton moving toward the left, holding camera B over his head at arm’s length.]

[Camera B: Reverse angle. Continuation of the left-to-right travelling shot of Wieland standing on the stairs. The camera moves more slowly this time. The roof of a car divides the frame in two, occupying the lower part of the screen. Wieland shoots straight ahead with her camera.] [The sound of the rolling camera comes to a stop.]

[Camera A: Close-up of Frampton’s head and his Bolex. He stops filming, removes the camera from in front of his face and ducks down behind the fence again.] [The sound of the spring mechanism being wound up.]

[Camera B: Reverse angle. Medium shot of Wieland. She sits on the stairs and uses the crank handle to wind up her camera’s spring mechanism. Once she is finished, she looks in front of her and places her hand in front of her zoom lens.] [The sound of a pushbutton being released to begin shooting.]

[End of scene.]

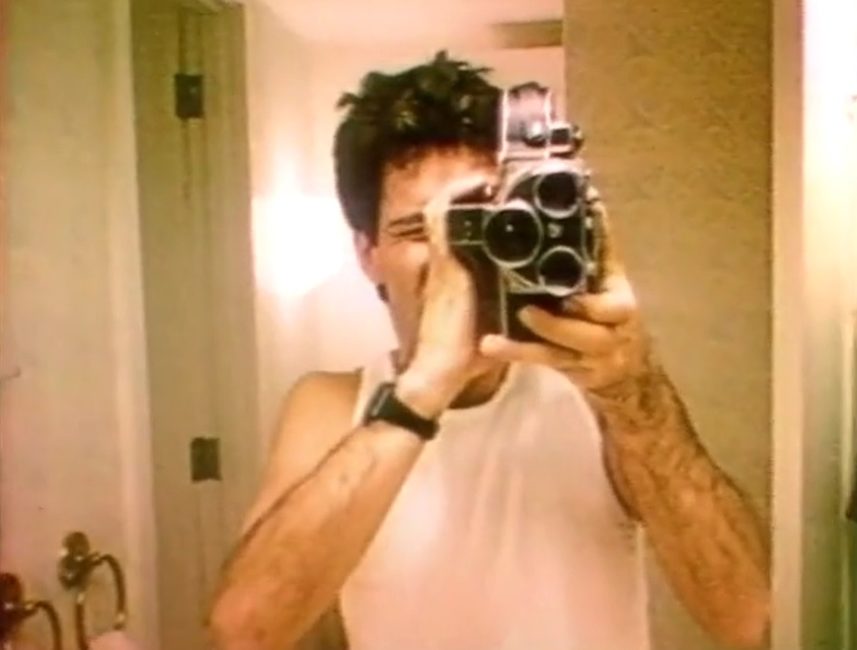

Yes Sir ! Madame directed by Robert Morin in 1994

© Coop Vidéo de Montréal, collection Cinémathèque québécoise

Born in Acadia of a francophone father and an anglophone mother, Earl Tremblay is going through an uncharacteristically Canadian identity crisis. Resolved to resolve it, he shoots the 19 rolls of film his filmmaker mother left him. His goal: to record his daily life, and try to find the same meaning in French and in English. As the reels get shot over the course of a journey that leads him from the Maritimes to Montréal, then to Ottawa as an MP, Tremblay watches his personality split and finally separate irrevocably (coopvideo.ca).

Yes Sir ! Madame

In Yes Sir! Madame, the video portrait of Robert Morin blends reality with fantasy. The camera through which he views the world becomes his confidante. It plays its own role in the movie and becomes part of the action it records.

Yes Sir ! Madame directed by Robert Morin in 1994

© Coop Vidéo de Montréal, collection Cinémathèque québécoise

Born in Acadia of a francophone father and an anglophone mother, Earl Tremblay is going through an uncharacteristically Canadian identity crisis. Resolved to resolve it, he shoots the 19 rolls of film his filmmaker mother left him. His goal: to record his daily life, and try to find the same meaning in French and in English. As the reels get shot over the course of a journey that leads him from the Maritimes to Montréal, then to Ottawa as an MP, Tremblay watches his personality split and finally separate irrevocably (coopvideo.ca).

Note: The information in square brackets describes the audio and visual content of the clip. The rest of the text corresponds to the inner monologue of the main character, added as a voice-over, commenting on the images on screen. The French passages in the video have been freely translated and are written in italics.

[1:07 minute sequence.]

[Indoors, evening, hotel room. Colour. Throughout the entire clip, the sound of the rolling camera can be heard.]

[Close-up of a photographic portrait of Brian Mulroney that is hung on the wall.]

But the boss didn’t seem to mind.

[Close-up of a man sitting on a bed with his back to the wall and his legs stretched out in front of him. He is still dressed in his shirt, tie, pants and eyeglasses.] [Yawning sound.] [He yawns as he looks at a newspaper.]

[Zoom in to a CRT television showing footage of Brian Mulroney celebrating his election victory with his family. The image on the television is black and white, with a bluish tint, and flickers from top to bottom. The zoom stops on Mulroney.]

When everybody left, I stayed up for a while and kept the partying alive with the Prime Minister and his family. [The man begins to sing.] C’est à ton tour, mon cher menton! [It’s now your turn, my dearest chin!]

[The TV is now showing a scene from an erotic film. The image is slightly blurry and has a yellow tint, preventing the action from being seen clearly.]

Il a fallu que tout le monde s’en aille pour pouvoir écouter une émission un peu plus représentative du monde de la politique. [I had to wait for everyone to leave before I could watch a show that was a bit more representative of the political world.]

[In a static wide-angle shot, the character is lying down filming the television and his own feet on the bed. The erotic film is still playing.]

That night, I went to bed happy and yet a bit… a bit lonely.

[The camera now turns to the wall, where there is a huge photograph of Mulroney and his wife. A white flash indicates that the reel has ended. In the next shot, the light is brighter and it is now daytime. Despite the temporal ellipsis, the camera is still aimed at the photograph, then it moves back to the TV, which is now turned off.]

Le lendemain matin, je m’suis réveillé avec un arrière-goût de pouvoir au fond de la gorge. [The next morning, I woke up with an aftertaste of power in the back of my throat.]

[The man, who is now in the bathroom in his underwear with his Bolex in his hand and his eye glued to the viewfinder, moves toward the mirrors. He moves closer to the central mirror while filming the reflection of his face.]

The next morning, I woke up ready to face my responsibilities. J’suis allé dans la salle de bains [I went into the bathroom] but, instead…

[He rotates to his left without stopping the camera. A second mirror placed at an angle creates a Droste effect: His reflection is repeated ad infinitum while decreasing in size, thanks to the play of the mirrors. This effect gives the impression that there are several people in line to the left of the protagonist.]

… I faced us, and there was a lot of them. On s’est fait peur pour vrai. [We scared each other for real.] We were all there. On était tous là. [ We were all there. ] All the pea-soupers on one side…

[He then rotates to his right and repeats the Droste effect with a third mirror.]

… pis toutes les têtes carrées de l’autre bord. [and all the square heads on the other.] The fight would have been a massacre. La bataille aurait pu être mortelle pour tout l’monde. [The battle could have been fatal for everyone.]

[He returns to the centre.]

The only reasonable solution was to split. Fait qu’on a décidé de se séparer. [So, we decided to part ways.] For good. Pour de bon. [For good.]

[The image cuts out and the screen turns blue.]

Yes, sir! Oui Madame! [Yes, madame!] Bonne chance! [Good luck!]

[The image cuts to black.]

Good luck! Chacun sa vie, chacun sa bobine. [To each his own life, and to each his own reel.] Ok. So, who’s gonna start.

[End of scene.]

The origins of an invention: Swiss ingenuity

The complexity and precision of the Bolex have their roots in Swiss watchmaking.

The Paillard company, which launched the Bolex H16, initially produced music boxes, gramophones and typewriters in the Swiss tradition of precision devices. However, in the late 1920s, the company decided to diversify its activities. It purchased the cameras, laboratories and numerous patents of engineer Jacques Bogopolsky, inventor of the Auto Ciné Model A and B cameras, which were intended to be transportable and “automatic.”

Bogopolsky, Jacques. 1928. Exposé d’invention pour un appareil automatique pour la prise de vues cinématographiques [Invention statement for an automatic apparatus for cinematographic photography]. No.124365. Geneva, Switzerland. 6 p.

Public domain

Invention statement for an automatic apparatus for cinematographic photography

This six-page patent protects the intellectual property of the inventor and guarantees the inventor’s exclusive rights to the patented invention. In the appendix, it contains six drawings of the camera and its parts. In the patent, Bogopolsky, a self-taught inventor, states his intention to build a camera that features automatic functions and a spring motor and can be used with different film formats.

Some of these features were retained by Paillard for the Bolex H16.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Bogopolsky, Jacques. 1928. Exposé d’invention pour un appareil automatique pour la prise de vues cinématographiques [Invention statement for an automatic apparatus for cinematographic photography]. No.124365. Geneva, Switzerland. 6 p.

Public domain

Translation of selected excerpts from the patent:

“The strength of the clockwork spring lever is constrained by the weight of this device, which must be portable.”

“Claim: Automatic apparatus for cinematographic photography characterized by a sectioned box in a double-T shape constituting a frame, a central partition supporting the components and dividing said box into two compartments, the first one containing the spring drive motor and gear train, and the second, completely isolated from the first by said partition, comprising the film, the components for its transport and the exposure chamber, each compartment being independently accessible.”

“According to the claim, apparatus characterized by a footage counter and equipped with visual and auditory control components to follow the progress of the film visually and aurally.”

[Translation]

Paillard wished to create a multi-functional camera. The company bucked the prevailing trend of creating complex cameras for professionals, and instead designed cameras that were easy for inexperienced users to operate. The Pathé Baby, created in 1923, was a good example of this. This very small camera, which predated the Bolex by about 10 years, was designed to be as simple as possible for non-professionals to use. It was so light that it had to be mounted and stabilized on a tripod..

Photograph of the Pathé Baby, from the collections of the Cinémathèque québécoise.

TECHNÈS – CC BY-SA 4.0

This small metal camera measured 11 cm x 10 cm x 5 cm and weighed 615 g. It used 9 mm film for non-professional cameras. It was quite different from the Bolex in its main features. Its functions were quite limited. Even the very wide-angle lens did not require any adjustment; everything was in focus.

Paillard launched the Bolex model H16 in 1935, after five years of development. Some of its working parts were directly inspired by Swiss clockwork, which is renowned for its quality and precision.

The camera is identifiable by its spring drive motor, which must be wound every 40 seconds, and by its lenses, which are mounted on a semicircular turret.

Standard model Bolex H16. This model is still used by students at the Université de Montréal. The semicircular turret and the three lenses are clearly shown.

TECHNÈS – CC BY-SA 4.0

The H16 was a commercial success in the 1960s, both in the USA and elsewhere. Its arrival on the market marked a turning point for the use of 16 mm film as a professional format. Until then, professionals had used 35 mm film for its superior quality. The versatility of the Bolex H16 encouraged them to work with 16 mm film on a more regular basis. Even today, there is still a Bolex workshop in Switzerland that repairs and offers maintenance for this camera.

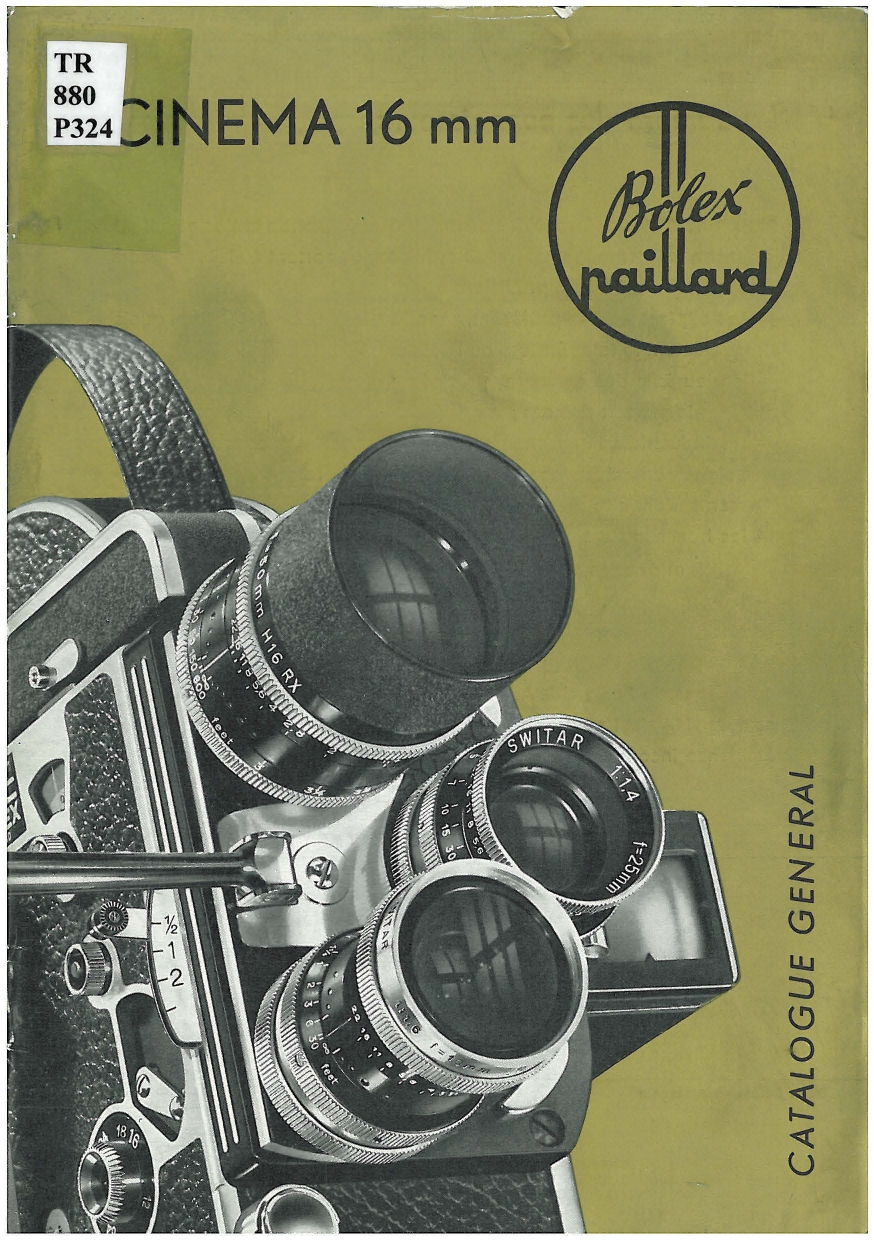

Anon. 1959. Paillard Bolex 16 mm Camera Catalogue. Switzerland. 16 p. TR.880.P324. Cinémathèque québécoise.

pdf (7.63 MB)Paillard Bolex 16 mm camera catalogue

This sixteen-page catalogue presents the brand’s line of 16 mm cameras. It highlights the features of the cameras and their various accessories, identifies compatible lenses and includes drawings and photographs for illustrative purposes.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Anon. 1959. Paillard Bolex 16 mm Camera Catalogue. Switzerland. 16 p. TR.880.P324. Cinémathèque québécoise.

pdf (7.63 MB)Translation of selected excerpts:

The new H16 Reflex, a masterpiece of mechanical and optical precision, is the most complete and versatile 16 mm camera available. It can perform all types of professional effects and stands out for its reflex viewfinder and variable shutter.

The H16’s possibilities are endless. For its users, nothing is impossible. Tools such as slow motion, fast motion, frame by frame viewing, stills, snapshots, full reverse motion, frame counter and variable shutter are all at their disposal to enhance and successfully create their films. Titling, special effects, dissolves, crossfades, ultra fast motion, animation of inert subjects, cartoons, scientific films and professional cinematic effects are all possible with this camera.

Bolex technical data sheet

![The title “Organes de la caméra H16 Reflex [Parts of the H16 Reflex Camera]” is printed across the top of the page above drawings of the camera’s main components, each of which is numbered for reference to the legend.](https://macameraetmoi.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Bolex-H16-Rex-5_collections-Francois-Lemai_carrousel8-976x0-c-default.jpg)

Which features of this light, versatile, automatic camera make it suitable for portraits and creative experimentation?

Specifications

- Measurements

- 21,50 cm x 15,24 cm x 7,2 cm.

- Weight

- Approximately 2.5 kg without the lens, which is relatively light.

- Materials

- Interior made of robust materials: duralumin, leather and chrome.

- Frame rate

- A 30-metre reel of film, equivalent to approximately four minutes of shooting at a rate of 16 frames per second. Silent.

Components and accessories

- Motor

- The Bolex H16 is self-powered. Electricity is not required. It features a spring drive motor that must be wound every 40 seconds using a small handle on the side.

- Three lenses, from 10 mm to 150 mm, or a zoom lens

- Mounted on a semicircular turret that allows lenses to be changed quickly during shoots, with no need for additional operations.

- Viewing system: Integrated optical viewer with reflex finder

- The reflex finder allows the filmmaker to see exactly what is recorded onto the film. However, light is only partially directed to the viewing system.

- 16 mm film

- Both colour and black and white 16 mm film can be used. The reels are called ‘daylight spools’ because they can be loaded into the camera in full daylight. They eliminate the need to load the film in darkness to protect the film from the light.

- Handle

- For carrying the camera and for easier handling

- RX fader for reflex lenses only

- This accessory makes dissolves easier and more fluid.

Features

- Multiple frame rates

- The frame rate can be changed from 8 frames per second (fps) to 64 fps, meaning that slow motion and fast motion can be planned at the time of recording.

- Frame counter

- Frame counter that allows effects to be added at the time of shooting. The film can be reversed for overlays, lap dissolves, slow motion and fast motion.

- No sound recording system

- This camera is relatively noisy. A mechanical clicking sound can be heard every 10 inches or so (at 16 fps). It allows the camera operator to quickly calculate the remaining footage when adding in-camera effects requiring precision

- It has a semi-automatic film loading system, which speeds up and simplifies the process.

- The Bolex is recognized for its precision, consistency and ability to withstand extreme temperatures.

Operation and handling

The Bolex allows filmmakers to remain close to both their cameras and their subjects. It provides them with great freedom of movement and serves as an extension of their eyes and bodies. Operators often develop a very strong relationship with their cameras.

However, the device is quite noisy and can disrupt sound recordings. In addition, a mechanical clicking sound can be heard when the camera is in use. It keeps track of the exposed film, allowing effects to be added with great precision, but increases the camera’s noisiness.

The Bolex can be used indoors or outdoors, in any conditions. This camera is both portable and adaptable, making it a solid choice for many types of professional operators, as well as for amateurs with a solid knowledge of photography.

The Bolex H16 must be held with both hands. The right hand is positioned underneath the camera, on the base plate, with the index finger on the release button that starts the film rolling. The left hand passes through the leather handle to grip the top of the camera. The camera is light enough to allow operators to move around easily, but heavy enough to keeps camera movements controlled. The spring drive motor must be wound approximately every 40 seconds and the camera can only hold 30 metres of film. This means that in addition to having to complete a number of operations before shooting, operators must also take the time limit into consideration. They have to contend with short shoots.

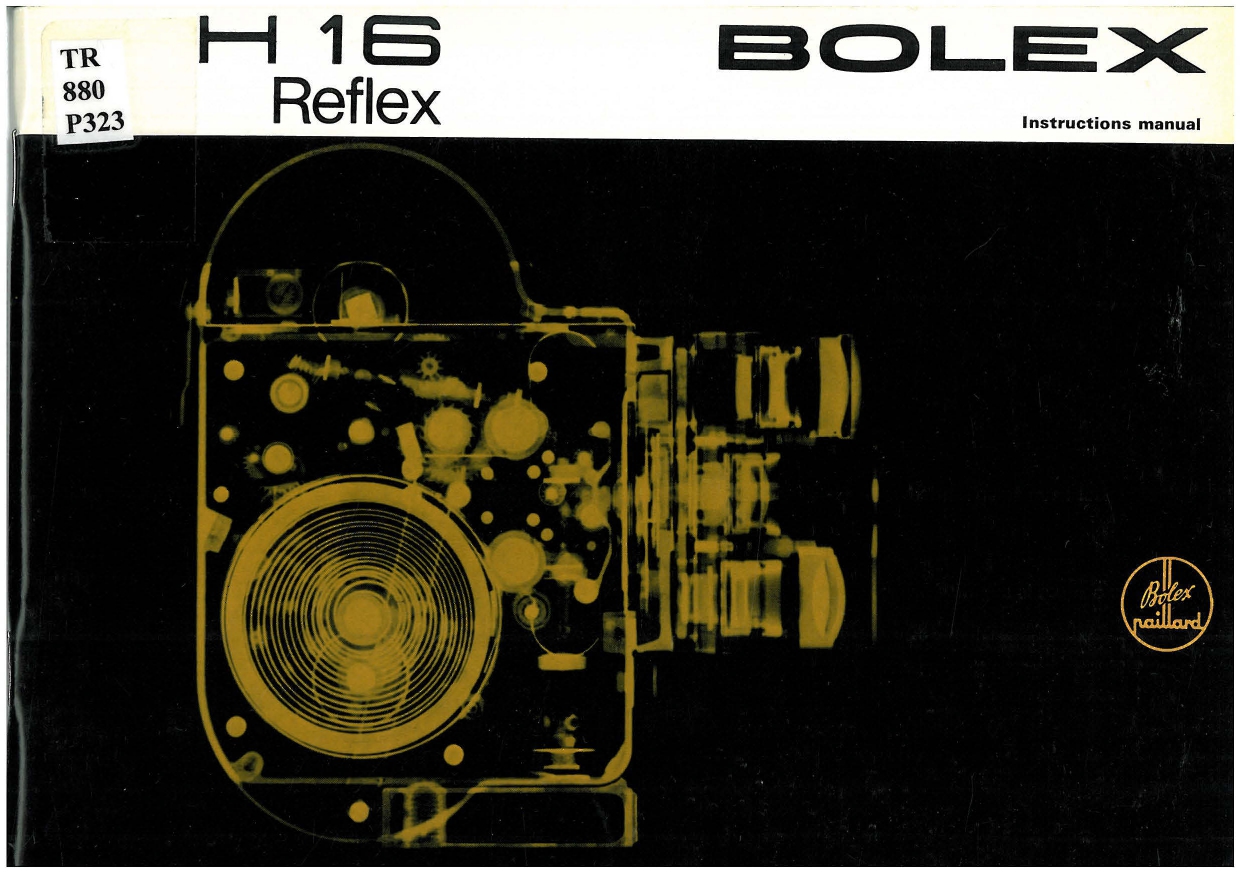

Anon. 1956. H16 Reflex Camera Instruction Manual. TR.880.P323. Cinémathèque québécoise.

Public domain

pdf (16.98 MB)

H16 Reflex instruction manual. From the collections of the Cinémathèque québécoise.

This 51-page manual provides detailed descriptions of the camera’s various components, as well as how to use them. It outlines the steps that must be taken before and after shooting, along with practical tips for filming and adding effects at the time of the shoot.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Anon. 1956. H16 Reflex Camera Instruction Manual. TR.880.P323. Cinémathèque québécoise.

Public domain

pdf (16.98 MB)

Transcript of excerpts from the instruction manual:

Do not start filming before having thoroughly read this booklet and studying the operation and various settings of your camera. Here are several rules we suggest you follow when shooting your first films.

The camera should be held absolutely steady, for the slightest jerk is amplified on the screen and results in unsteady pictures. Rest the camera against the forehead or cheek, stand with the legs wide apart, and where possible, lean against a firm support, such as a wall or tree trunk. Move the camera slowly and smoothly. It is advisable to use a grip and, if possible, a tripod.

To frame a shot using a camera equipped with a reflex finder, the operator’s eye must be placed against the viewfinder. This changes the relationship between the operator and the camera. Being able to see what is being filmed allows filmmakers to be much more spontaneous, because they know exactly what is in the frame. The filmmaker can see what is being filmed and can move about more freely.

It is interesting to note that early instruction manuals highlighted the importance of keeping the camera as steady as possible to capture “professional” images. However, a shift occurred in the 1960s and manuals began to place more emphasis on the portability and experimental possibilities of the camera.

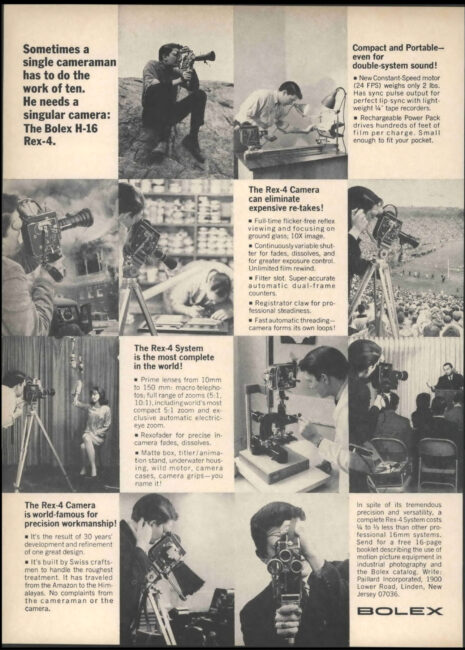

Bolex Rex-4 pamphlet as it appeared in American Cinematographer in 1966. The title states, “Sometimes a single cameraman has to do the work of ten. He needs a singular camera: The Bolex H-16 Rex-4.”

Public domain

Who uses the Bolex?

This camera appeals to many types of users: amateurs with solid photography skills, explorers, scientists, anthropologists, artists and filmmakers. Today, it is widely used for family movies and experimental films, as well as in many North American schools.

The first Bolex H16 was released in 1935 at a cost of 565 Swiss francs— equivalent to more than $4,000 of today’s Canadian dollars. Only one lens was included in the price. The other two lenses, plus the accessories, added to the cost of the camera.

“If we consider that the average salary of a Paillard worker in 1935 was 1 franc 23 centimes an hour, the purchase of an H camera represented more than a month and a half’s wages” (Dulac 2016). The camera was therefore not accessible to those with lower incomes. In 1970, its price was lowered, making it more appealing to young amateur filmmakers without a lot of money.

Some of the biggest names in Québécois, American and European cinema of the past few decades started out using Bolexes. They include Jonas Mekas, Maya Deren, Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, Michel Brault, Claude Jutra, Spike Lee and Peter Jackson.

Many amateur filmmakers employed these easy-to-use cameras to record the moments of their lives, both the mundane and the extraordinary. The camera allowed them to express their views and emotions regarding the people and objects that surrounded them. Others, driven by the desire to create, took advantage of the camera’s technical features to express themselves and produce works of art. They explored its inner workings to devise new visual concepts. [Translation]

(Dulac, Sorrel and Tralongo 2017)

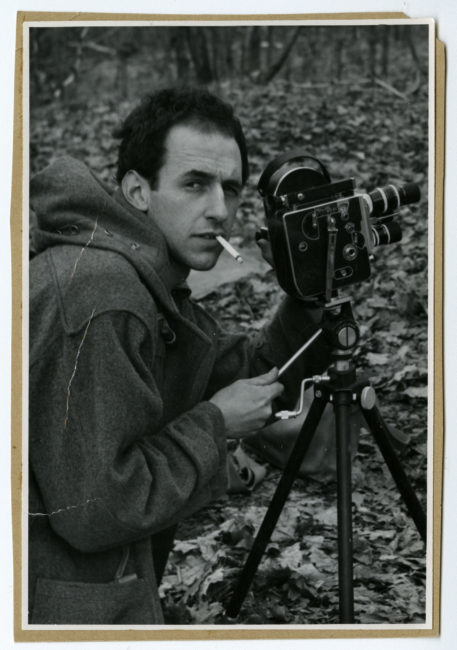

Photograph of Michel Brault with a Bolex. n.d. The Bolex is mounted on a tripod. Cinémathèque québécoise collection, 2000.0005.PH01

Photograph of Wendy Michener and Joyce Wieland in 1969.

Copyright: York University Library, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Joyce Wieland fonds, ASC07123

Still frame from the film L’aventure Bolex by Alyssa Bolsey. Experimental filmmaker Barbara Hammer holds her Bolex.

©AKKA Films

The Bolex’s small size and easy handling made it ideal for filming oneself and one’s friends and family, creating intimate portraits of everyday life, capturing important memories and revealing a subject’s personality or emotions, much like smartphones do today.

Additional resources

This motion picture glossary will help you better understand some of the terminology used.

Are you the inquisitive type? Would you like to learn more about the Bolex and the filmmakers who used it? The following websites will provide you with additional information.

- Trailer for Beyond the Bolex, produced by Alyssa Bolsey in 2018.

- Clip from a film entitled Paillard Bolex by Alexandre Favre. In progress. (English subtitles available by clicking the “CC” box on the image.)

- Travelling exhibit entitled “La machine Bolex : Les horizons amateurs du cinéma [The Bolex: Amateur Cinema Horizons].” 2017 to 2020 in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Bourgogne–Franche-Comté and Switzerland. Developed by the Université de Lausanne and the Cinémathèque des Pays de Savoie et de l’Ain.

- Website featuring all the Paillard Bolex brand’s brochures and instruction manuals.

Bibliography

Bogopolsky, Jacques. 1928. Exposé d’invention pour un appareil automatique pour la prise de vues cinématographiques. No.124365. Geneva, Switzerland. 6 pages.

Dulac, Nicolas. “Le dispositif-Bolex: Archives techniques, discours promotionnel et invention du cinéaste ‘professionnel-amateur’ [The Bolex: Promotional Discourse, Iconography and the Invention of the ‘Professional-Amateur’ Filmmaker].” Presented at the FSAC Annual Conference, Calgary, May 31, 2016.

Dulac, Nicolas, Vincent Sorrel and Stéphane Tralongo (Dir.). 2017. La machine Bolex : les horizons amateurs du cinéma. Exhibition catalogue 2017-2020. France: La Cinémathèque des Pays de Savoir et de l’Ain. Switzerland: Université de Lausanne.

Dulac, Nicolas, Vincent Sorrel, Stéphane Tralongo and Benoît Turquety (Dir.). 2020. “La machine Bolex. Les horizons amateurs du cinéma.” Encyclopédie raisonnée des techniques du cinéma. Under the direction of André Gaudreault, Laurent Le Forestier and Gilles Mouëllic. www.encyclo-technes.org/fr/parcours/tous/bolex.

Perret, Thomas and Roland Cosandy. 2013. Paillard-Bolex-Boolsky: la caméra de Paillard et Cie SA, le cinéma de Jacques Boolsky. Yverdon-les-Bains: Éditions de la Thièle.

Want to find out more?

Take an audio journey into the world of this device.

![Page one of the patent—called an exposé d’invention [invention statement]—for the camera that would later become the Auto Ciné Model A. It features Bogopolsky’s name, the patent number, the place and the date. The remainder of the page contains a description of the camera.](https://macameraetmoi.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Brevet_Bogopolsky-Jacques_1928_thumbnail.jpg)