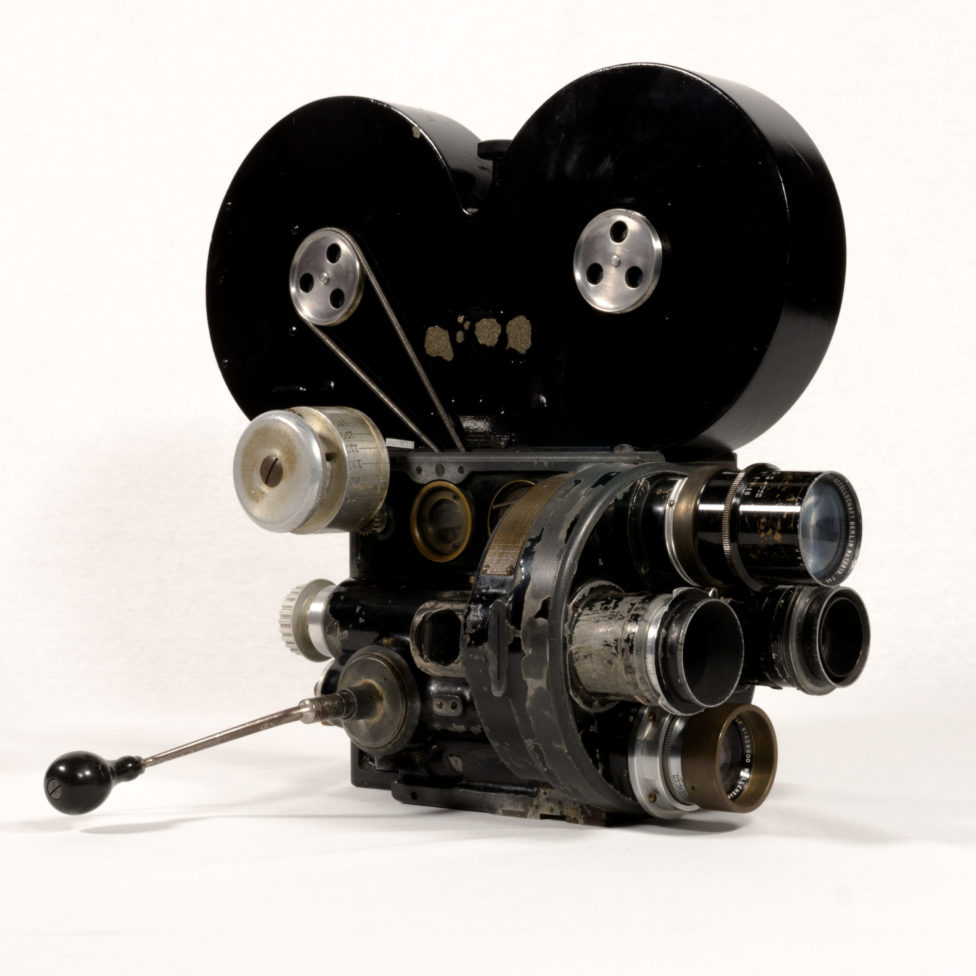

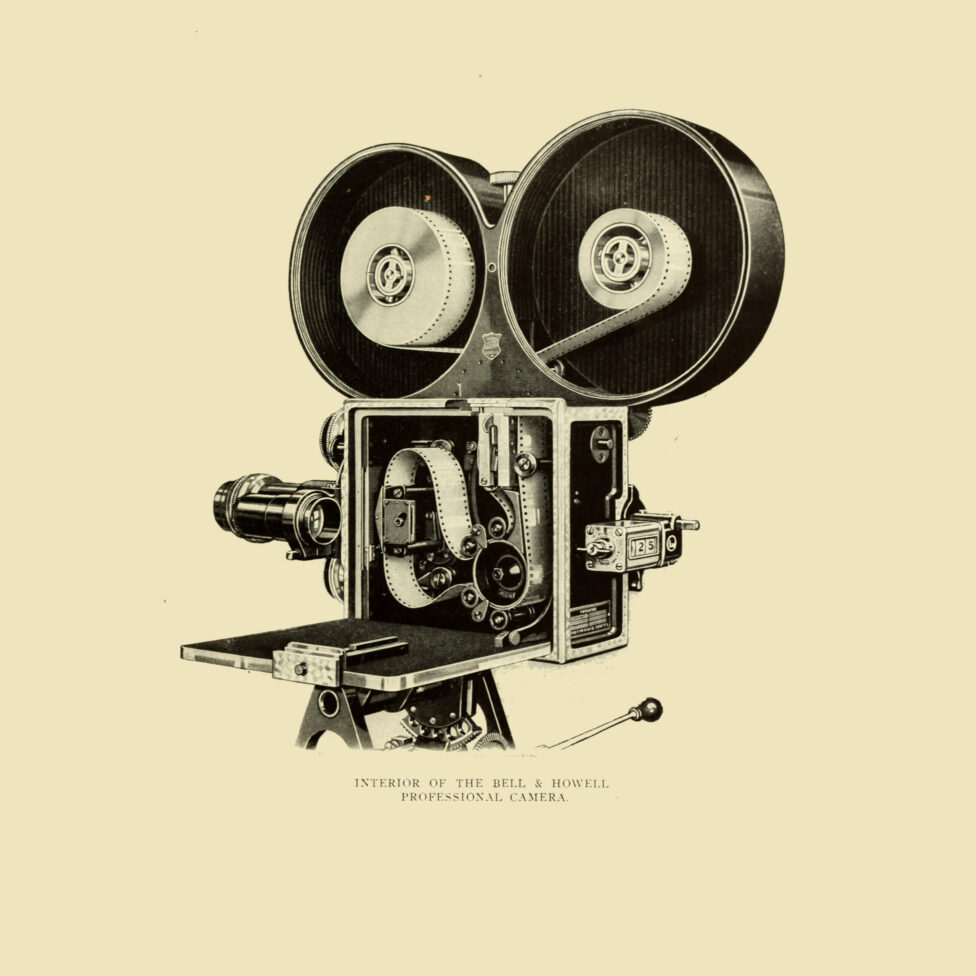

From the late 1910s to the late 1920s, the Bell & Howell was the most widely used camera in Hollywood studios. Its ear-shaped magazines earned it the nickname “Mickey Mouse Ears.” You may be familiar with its silhouette because the Bell & Howell is the icon used as the movie camera emoji.

Discover how this large, rugged camera changed the way we see the world. This iconic camera significantly influenced the practices of professional filmmakers. Of the six cameras on this site, it was the least portable, but it will allow you to understand, by way of comparison, the evolution of other portable cameras. In what context was it invented? How did it work? Who operated the camera in those days? You’ll find the answers to all these questions here, and you’ll be able to watch some Canadian films shot with the Bell & Howell.

Refer to the “Additional Resources” section to see a glossary of technical terms.

The birth of cinema as an institution

In the early 1900s, filmmakers were in search of more precise cameras with which to shoot their films. Enter the Bell & Howell!

Known for its high quality, precision, and beautiful, sharp, stable images, the Bell & Howell was viewed as the leading edge in professional cameras. However, it was very heavy and difficult to transport.

Imposing, robust and made of metal, the Bell & Howell used 35 mm film and allowed operators to view their shots before recording them. They were able to frame and focus their shots using an ingenious system detailed below. This heavy camera was mounted on a tripod, enabling operators and their professional assistants to record very stable images.

From the late 1910s to the late 1920s, the Bell & Howell was the most widely used camera in Hollywood studios. Its production ceased in 1958. Several of these cameras were still in use in animation studios at the turn of this century.

The precision and stability of the Bell & Howell made it the studio camera of choice, and it greatly influenced the practices and aesthetics of cinema. In the early glory days of silent film, it was a fixture in the major Hollywood studios that established the codes of cinema still in effect today.

Canadian films shot with the Bell & Howell

The Bell & Howell was also used in Canada. The Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau (CGMPB) employed these cameras for both studio and outdoor shoots. Founded in 1918, the CGMPB was “the first national film production unit in the world. Its purpose was to produce films that promoted Canadian trade and industry […] It was absorbed into the National Film Board (NFB) in 1941 […] The Bureau maintained the largest studio and post-production facility in Canada.”1 The Bureau also maintained close ties with Hollywood studios, enabling them to invest in the development of the Canadian film industry.

1 https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-government-motion-picture-bureau

Carry on, Sergeant ! directed by Bruce Bairnsfather in 1928.

Public domain

An ordinary Canadian man leaves his wife at home to join a battalion. At the same time, young men from wealthy families enlist and become officers. Glimpses of World War I and of the Battle of Ypres in Belgium.

Carry on, Sergeant !

Filmed at the Ontario Motion Picture Bureau’s studios in Trenton, Ontario, this film had a colossal budget for its time: half a million Canadian dollars. Gordon Sparling, a pioneer of Canadian cinema (he was hired by the Ontario Motion Picture Bureau, then worked for the Associated Screen News and the NFB) was the camera operator.

In the selected clip, the action takes place in a small café. To shoot this movie, the camera was kept relatively stationary. Its heavy weight and the challenges of moving it smoothly are visible in this pan shot. In contrast, the still frames are of good quality.

Carry on, Sergeant ! directed by Bruce Bairnsfather in 1928.

Public domain

An ordinary Canadian man leaves his wife at home to join a battalion. At the same time, young men from wealthy families enlist and become officers. Glimpses of World War I and of the Battle of Ypres in Belgium.

Note: The information in square brackets describes the visual content of the clip, as well as the intertitles. This is a silent film.

[1:21 minute sequence.]

[The interior of a tavern. Black and white.]

[There are several clients in the establishment, mainly soldiers and women keeping them company. The camera pans from left to right in a wide-angle shot and stops at a table in the foreground, which is occupied by two men in civilian clothing and a woman. They drink, smoke cigarettes and converse. In the background there are soldiers, viewed from behind, leaning on the bar. They order drinks from the waitress while an officer, viewed from the front, chats with an employee.]

[Medium shot of the waitress at the bar. She is serving drinks when suddenly her eyes light up at the sight of someone who is off camera. She smooths down her hair and clothes, then steps out from behind the bar to walk toward the person.]

[Fade to black] [Image showing a drawing of two young women in three-quarter profile, wearing hats, superimposed by the intertitle.]

[Intertitle: That night, with leave cancelled once again, the war-worn MacKay comes to the Estaminet … Even Estaminet girls can help one to endure and forget…]

[The waitress joins the man, MacKay, who takes her hands in his, holds her outstretched arms, spins her around in a pirouette and lifts her onto the bar. They begin to chat with their arms around each other. A second man approaches but is pushed away by MacKay. The waitress lights MacKay’s pipe with a match. They are about to kiss when another soldier calls out to MacKay.]

[Fade to black] [Image showing a drawing of a military epaulette, superimposed by the intertitle.]

[Intertitle: Sergeant MacKay!]

[End of scene.]

[Fondu au noir]

[Dessin d’illustration sur lequel repose l’intertitre représentant deux jeunes femmes de profil trois quart, arborant des chapeaux.]

[That night, with leave cancelled once again, the war-worn MacKay come to the Estaminet … Even Estaminet girls can help one to endure and forget…]

[La serveuse rejoint l’homme, MacKay, qui lui prend les mains, bras tendus, la fait tourner sur elle-même et l’assoit sur le bar. Ils s’enlacent et discutent. Un second homme s’approche, mais se fait repousser par MacKay. La serveuse allume la pipe de MacKay avec une allumette. Alors qu’ils s’apprêtent à s’embrasser, MacKay est interpellé par un autre soldat.]

[Fondu au noir]

[Dessin d’illustration sur lequel repose l’intertitre représentant une épaulette militaire]

[Sergeant MacKay!]

[Fin de l’extrait]

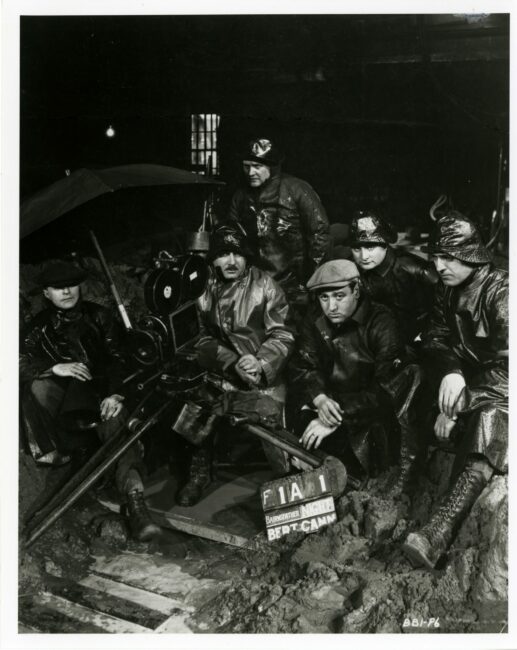

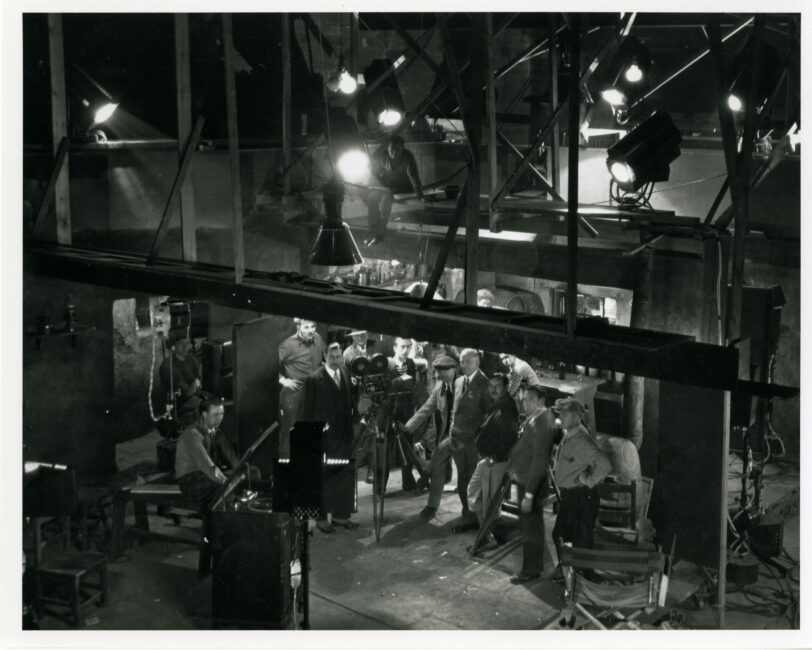

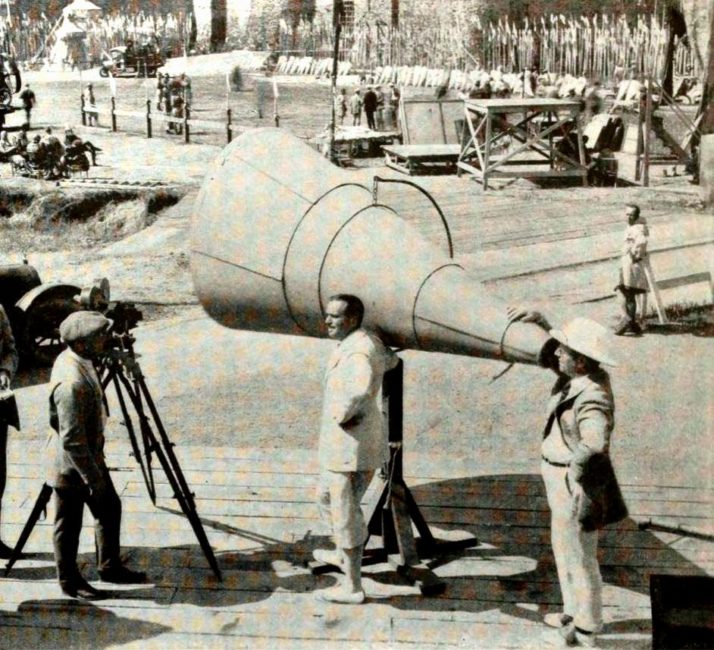

The film sets were created in studio, as can be seen in the following two photographs:

Photograph from the shoot of Carry on, Sergeant! The Bell & Howell sits on a tripod. The apparatus appears to be very stable, and therefore difficult to move. Cinémathèque québécoise 1995.0700.PH.08

Copyright: Public domain

Photograph from the shoot of Carry on, Sergeant! Cinémathèque québécoise 1995.0700.PH.03

Copyright: Public domain

Back to God’s Country directed by David M. Hartford in 1919

Public domain

The protagonist lives in the wilderness with her father. One day, evil men come to kidnap her. Her father is killed in the skirmish, but she manages to escape with her fiancé. (Programming from the Les Cinémas du Canada retrospective at the Georges Pompidou Centre).

Back to God’s Country

Parts of this film were shot in Faust, Alberta. The film stars Nell Shipman, a Canadian actress, writer, producer and director who was based in Hollywood. This clip exemplifies the high quality of the images produced by the Bell & Howell. The last image, which is an overlay of several shots, demonstrates the types of effects that could be achieved with this camera.

Some of the footage was shot outdoors in winter temperatures as low as -50 degrees Celsius. The hardy camera was left outdoors at all times, even at night, to avoid problems caused by temperature variations.

Back to God’s Country directed by David M. Hartford in 1919

Public domain

The protagonist lives in the wilderness with her father. One day, evil men come to kidnap her. Her father is killed in the skirmish, but she manages to escape with her fiancé. (Programming from the Les Cinémas du Canada retrospective at the Georges Pompidou Centre).

Note: The information in square brackets describes the visual content of the clip, as well as the intertitles. This is a silent film, shot in black and white but released on tinted stock.

[1:14 minute sequence.]

[The interior of a log cabin with animal hides on the walls. The film is tinted amber.]

[A man is lying in bed under a fur blanket, talking to a woman who approaches him and takes his hand. She looks out the window.]

[Long shot of a sunrise through the window.]

[Back to the two characters. They appear to be conversing. The woman, standing, looks back and forth between the man and the window while continuing to hold the man’s hand.]

[A brown Labrador-type dog approaches the door of the house from outside. It is wearing two collars.] [The woman kisses the man on the forehead.] [The dog scratches at the door. The woman opens the door, and the dog enters. The woman kneels down next to the dog and pets its head and muzzle.]

[Fade to black.]

[Intertitle: Wapi—dear old Wapi—we’re going home—home—and you are going with us….]

[Back to the woman, who is cuddling the dog.] [Iris out on the woman’s face.]

[Outdoors, wooded area near a pond. The film is tinted pink.]

[Photograph of a wooded area superimposed by the intertitle.]

[Intertitle: And then the old dream…]

[Fade to black.]

[A woman is playing with a bear cub beside a pond. A second bear swims around while a third one emerges from the pond.] [At the bottom centre of this image another image is superimposed, showing a woman inside a house in front of large wooden doors.]

[Intertitle: Come true]

[End of scene.]

The director of the Bureau, Ben Norrish, was also the director of the Associated Screen News of Canada (ASN), which was established in 1920. In those years, the ASN was behind most of Canada’s newsreels and corporate films. It closed its film production department in 1957.

The ASN owned several Bell & Howell cameras and regularly employed well-known Canadian camera operators.

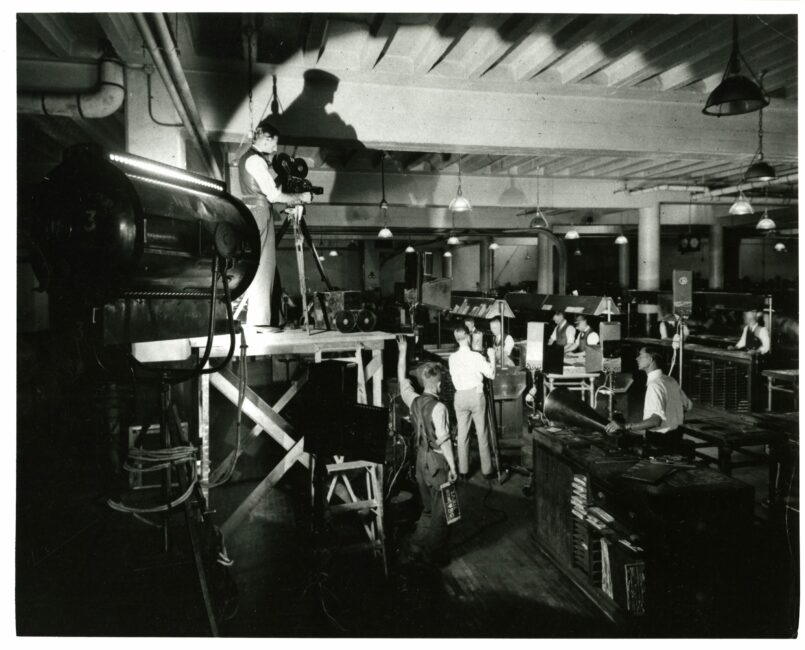

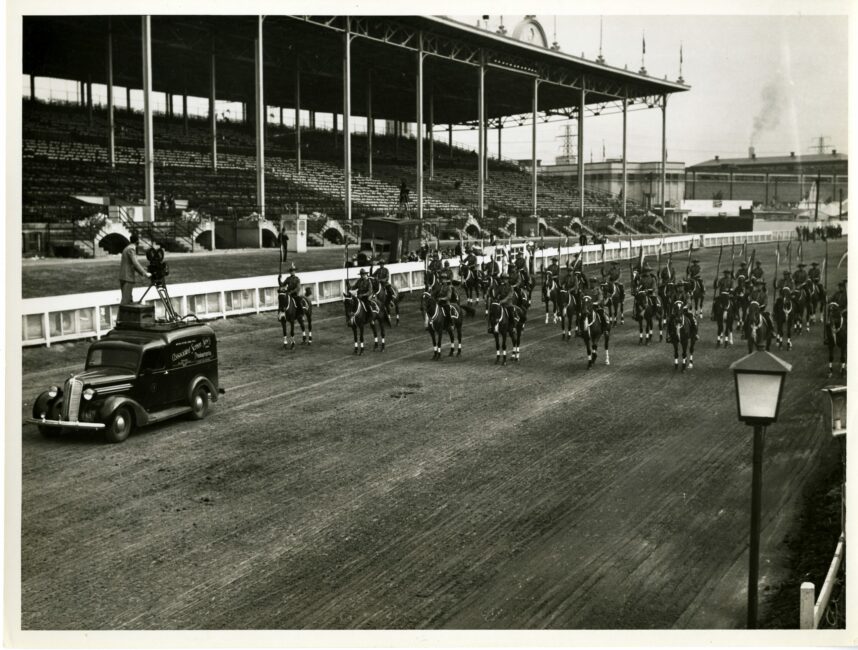

Some examples of indoor and outdoor film shoots:

Photograph of an Associated Screen News of Canada film shoot. Cinémathèque québécoise 1999.0861.PH.35

Copyright: Public domain

Photograph of an Associated Screen News of Canada film shoot. Cinémathèque québécoise 1999.0861.PH.21

Copyright: Public domain

Photograph of an Associated Screen News of Canada film shoot. Cinémathèque québécoise 1999.0861.PH.36

Copyright: Public domain

Photograph of an Associated Screen News of Canada film shoot. Cinémathèque québécoise 1999.0861.PH.01

Copyright: Public domain

The origins of an invention

The Bell & Howell is named after the two men who invented it: Donald J. Bell and Albert S. Howell.

In the early 1900s, when Chicago was the epicentre of the film industry, Donald J. Bell, a projectionist, and Albert S. Howell, an engineer in a projector parts factory, decided to form the Bell & Howell Company. The company specialized in the repair of movie equipment and the manufacture of film printers and perforators. The two men undertook their business with an understanding of the limitations of the machines and the expectations of the growing professional community. Their initial specialization influenced the future designs of the brand’s cameras. Bell & Howell’s perforations became the international benchmark.

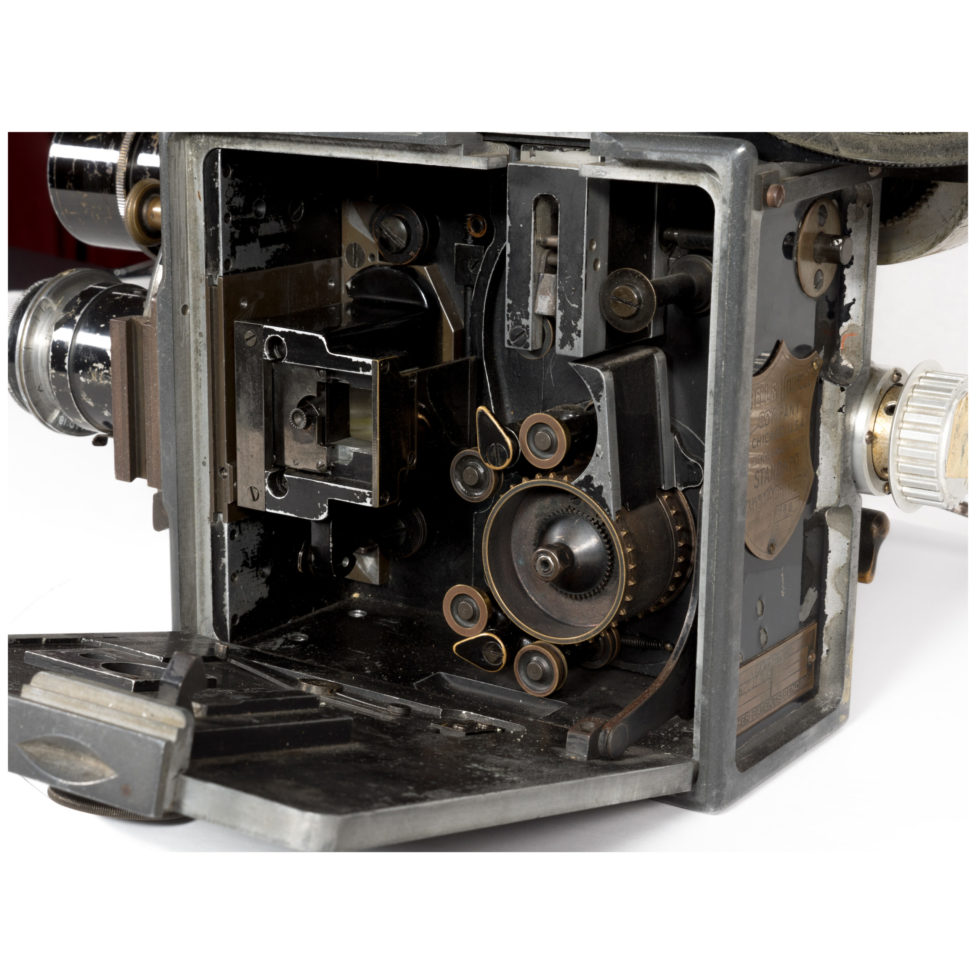

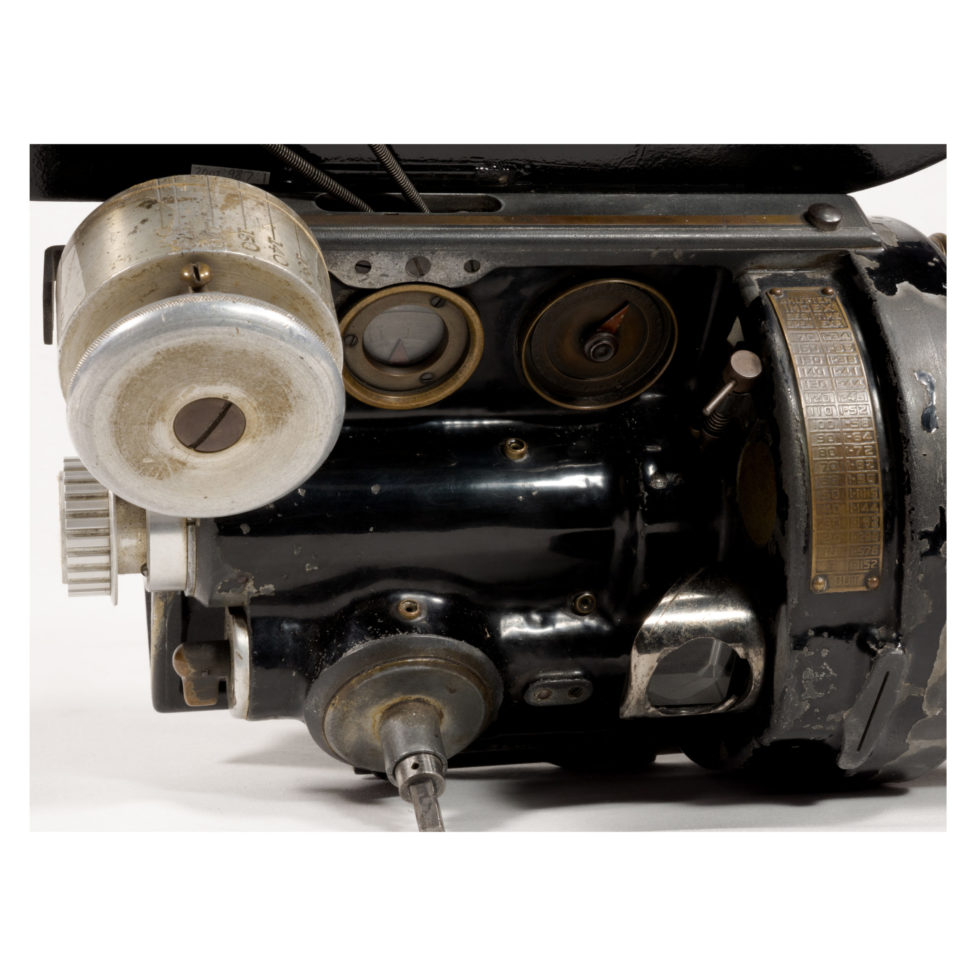

In 1912, Bell and Howell developed the 2709 Model B camera, known as the Standard Camera, whose high-performance film drive system continues to be the benchmark today. Its two claws advanced the film, and a press frame plated the film as it was exposed to light. This made it possible to achieve very precise effects at the time of filming.

The products and standards developed by the Bell & Howell Company in the first quarter of this century laid the cornerstone for most subsequent development in motion picture technology—professional and amateur—throughout the world, but especially in the United States. However, this historical paper will concentrate, in general, on the 35-mm gauge motion-picture cameras developed and built by the company, and in particular on one camera model, the Standard Model 2709.

Roberts, Laurence J. 1982. “Cameras and Systems: A History of Contributions from the Bell & Howell Co. (part.1).” SMPTE Journal, October: 934.

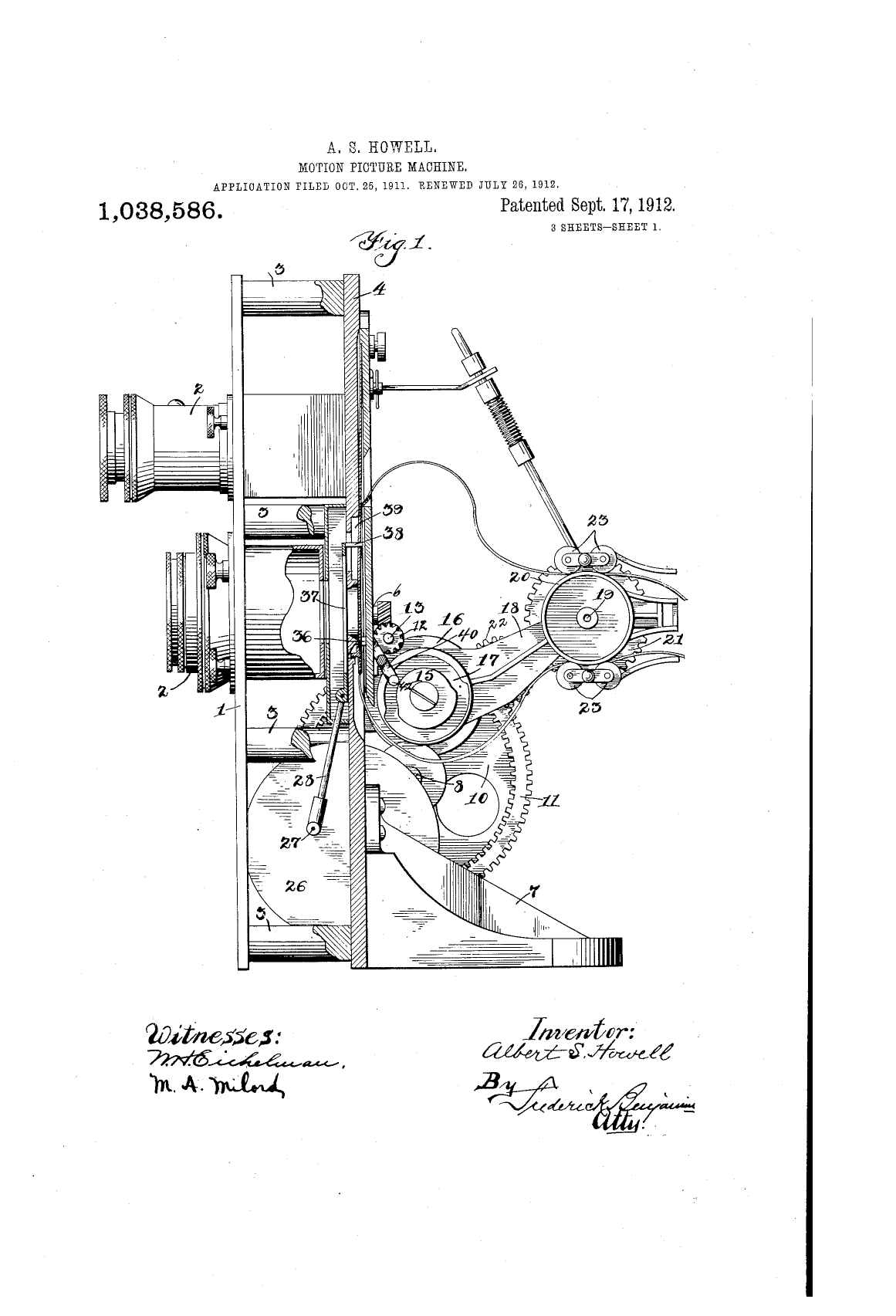

Howell, Albert S. 1911. Motion Picture Machine. Patent No. 1,038,586. United States Patent Office.

pdf (358.46 KB)Motion Picture Machine. Patent for Bell & Howell’s first wooden model.

This five-page patent, three pages of which contain illustrations, protects the intellectual property of the inventor and guarantees the inventor’s exclusive rights to the patented invention. In this document, Howell describes the internal drive mechanism, which was developed to allow greater precision during filming. This document refers to the first wooden version of the 2709. With the B model, adjustments were made: The body was entirely made of metal and the film drive mechanism was modified. Another notable difference was the location of the magazine. It was located inside the original model but on the exterior of the B model.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Howell, Albert S. 1911. Motion Picture Machine. Patent No. 1,038,586. United States Patent Office.

pdf (358.46 KB)Transcript of the conclusion of the patent:

Having thus described my invention, what I claim as new, is:

- A film feeding mechanism comprising a film guide way, means for shifting said guide way transversely to its direction, reciprocating pins adapted to extend into said guide way and engage film therein in one position of said guide way, and fixed pins adapted to extend into said guide way and engage said film in the other position.

- A film feeding mechanism comprising reciprocating pins, a flexible film guide way and means for flexing said guide way to bring it into and out of the path of reciprocation of said pins.

- A film feeding mechanism comprising pins, means for reciprocating said pins, a film guide way movable transversely to its direction, and means for moving said guide way into and out of the path of reciprocation of said pins.

The Bell & Howell Model B was the first metal camera to be widely used by studio operators.2 It was a great success and could compete with the wooden Pathé Professional camera.

2 Hollywood studios resembled much larger versions of Edison’s studio, which you saw on the Cinématographe info sheet.

In 1907, the year that Donald Bell and Albert Howell formed the Bell & Howell Co., the motion picture industry, then still in its formative years, was a collection of various film gauges and perforation standards. Films made in a particular country, or even city, or by a particular producer or studio, could not be exhibited except on machines made for that specific film. Needless to say, an international or even national distribution and exhibition of any film was in most cases impossible. Both Donald Bell and Albert Howell soon realized that a standardized gauge and perforation standard was mandatory. Were it not for their foresight and that of other pioneers, we might still have today a jumble of film gauges and formats, with every studio in the world making films for exhibition only on its own machines. This early standardization of the 35-mm film gauge, with four perforations per edge/frame, is to this day one of the few world standards in many areas.

Roberts, Laurence. J. 1982. “Cameras and Systems : A History of Contributions from the Bell & Howell Co. (part.1)”. SMPTE Journal, octobre, p. 934-935.

Photograph of the Pathé Professionnelle, from the collections of the George Eastman Museum. This camera was made of wood and was therefore less durable than the Bell & Howell, which was entirely made of metal.

TECHNÈS – CC BY-SA 4.0

This camera was widely used before the arrival of the Bell & Howell, and it continued to be used as a second camera on set:

“It took some time for the 2709 to become popular in Hollywood, due in the main to competition from the popular Pathé camera of the day. In many cases, when two cameras were needed (either for safety or for a duplicate negative or a foreign version), a combination of Pathé and 2709 cameras would be used on the same production” (Roberts 1982, 939).

Wikipedia entry on the camera (French only)

3D image of the Pathé Professional camera

Approximately 1,200 of these cameras were produced in total. This model was mainly used until the end of the 1920s and the arrival of the “sound films.”3 Production of this camera ceased in 1958.

In those days, the Bell & Howell cost around $2,000 USD—equal to about $72,000 CAD today. With the addition of various lenses and accessories, the total cost could be equivalent to that of a house. Aside from some of cinema’s biggest names, like Charlie Chaplin, only studios had the financial resources to purchase such expensive equipment.

3 The famous Jazz Singer, one of the first “talking picture,” was released in 1927.

Bell & Howell technical data sheet

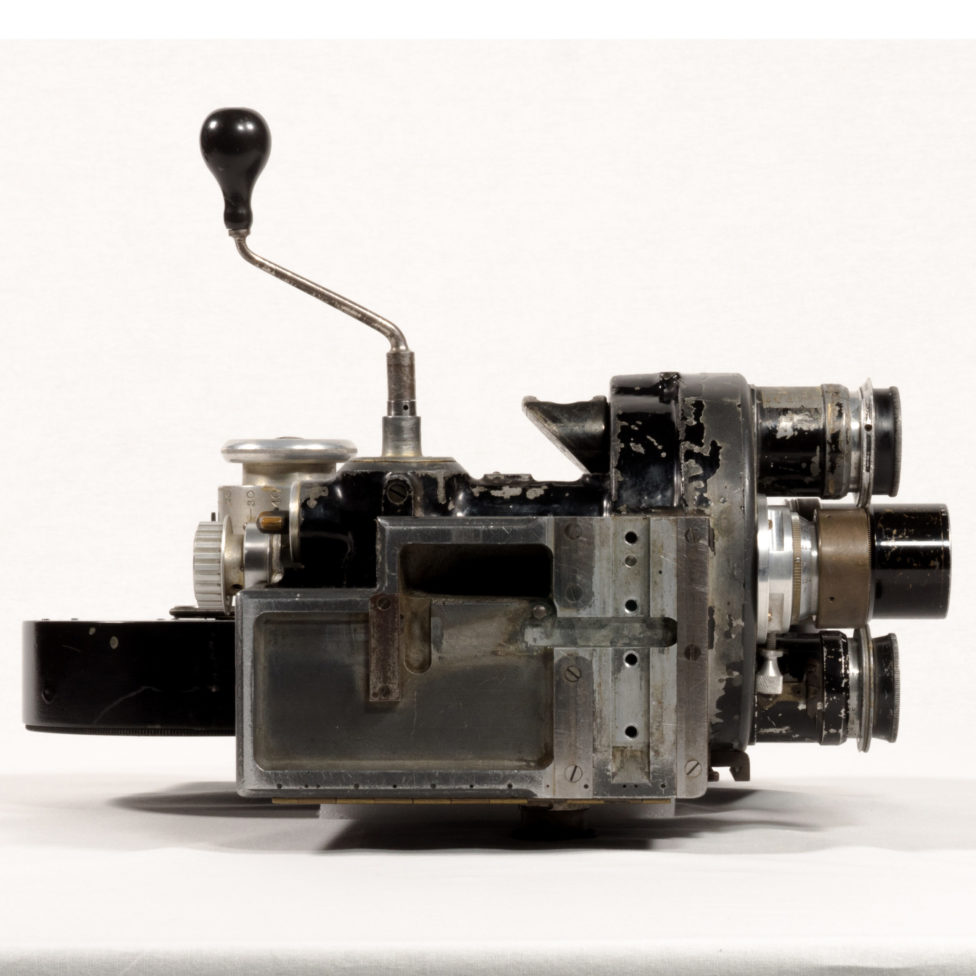

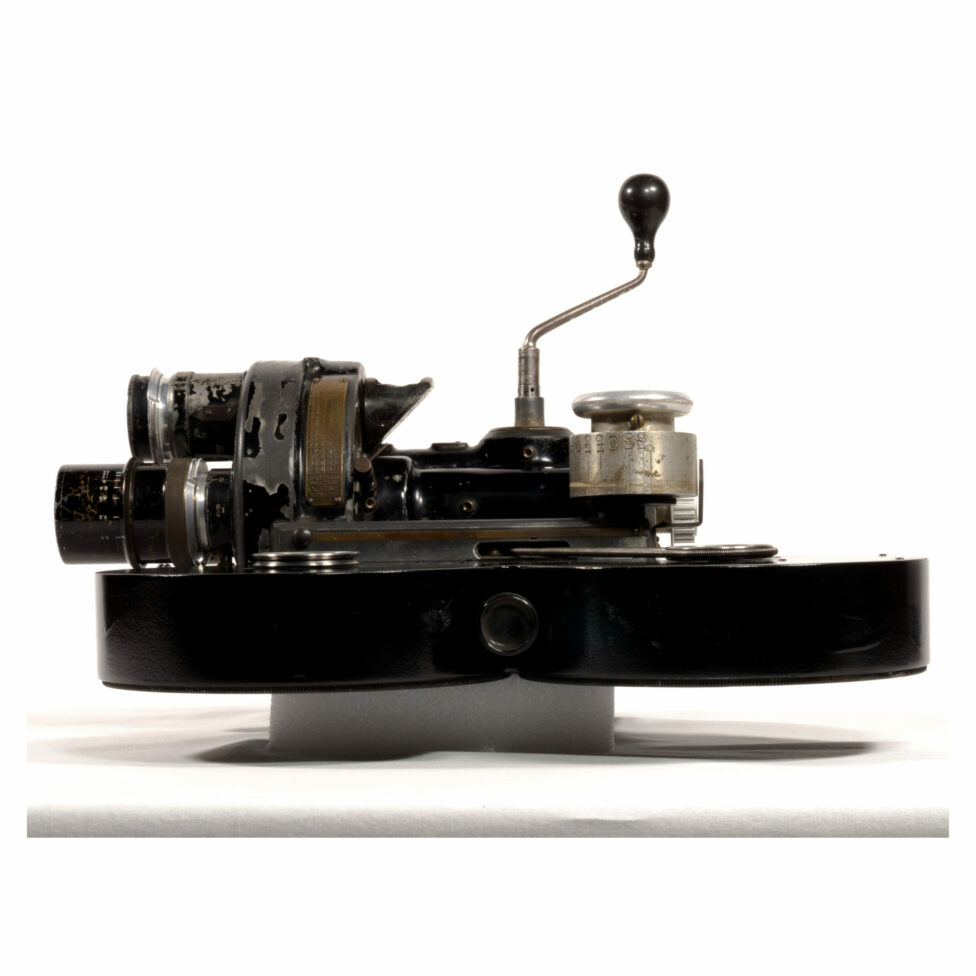

Which of this camera’s features made it so professional, precise and stable?

Specifications

- Measurements

- 38 x 18 x 38 cm

- Weight

- 12 kg, including lenses and magazine. 41 kg with the tripod and storage box. The camera’s weight provided it with great stability.

- Materials

- All metal, mainly aluminum.

- Frame rate

- Approximately 16 frames per second. The speed could be varied because the film was advanced by a crank handle powered by the operator.

Components and accessories

- Four lenses mounted on a rotating circular turret

- It was the first professional camera that allowed lenses to be changed quickly.

- Crank handle

- It had to be operated at a speed of two revolutions per second to achieve a frame rate of 16 fps (frames per second).

- Tripod weighing approximately 9 kg

- Equipped with two cranks for horizontal and vertical panning. The movements could be somewhat jerky.

- Reel of film

- Between 120 and 305 metres of 35 mm film—which would become the industry standard—providing up to 16 minutes of recording time without having to change the reel

- Footage counter

- A footage counter with the ability to rewind the film to make overlays—an effect that superimposes two images to form a single one—at the time of shooting.

Features

- Mécanisme pour stabiliser le défilement/arrêt de la pellicule.

- This component resulted in images of high quality and precision.

- Silent films

- Synchronized sound was possible with the addition of a motor and the use of a soundproof blimp and 305-metre soundproof magazines, but this was not the most suitable camera for making talking pictures.

Main disadvantages

- Its viewfinder displayed an inverted image.

- Its lens hood did not permit the insertion of filters, which consequently had to be mounted directly on the lenses.

Operation and handling

Instruction manuals for the professional cameras of those early days are very hard to find. Training took place in the field, with experienced camera operators.

The camera was operated by camera operators and assistants under the supervision of a director. For reasons of efficiency and profitability, each person on a film set had a narrowly defined role.

On the set of Robin Hood, Allan Dwan could be heard by 1,200 extras, thanks to the world’s largest megaphone, which measured four feet in diameter and ten feet in length. This image epitomizes the grandeur of studio moviemaking. Photograph from Photoplay magazine, 1922.

Copyright: Public domain

Before the crank handle could be turned, several steps had to be taken to set up the camera, such as loading the film in the magazines, framing the shot, measuring the aperture, focusing, etc.

This camera did not have a reflex finder, so once shooting began, it was not possible to see what was being filmed. However, it was equipped with a system for framing and focusing the shot before recording. A viewfinder allowed the operator to control what was recorded by the taking lens, which was located 180º from the viewing lens. It was therefore possible to frame and focus the shot through the viewfinder. The operator would then rotate the turret to place the lens in shooting mode. This produced a slight parallax (the frames were not identical), which could be troublesome when characters were close to the edge of the frame. In those cases, a special tripod was needed, or more specifically, a special tripod head, which worked in conjunction with the camera’s viewing system. The camera had two positions: one for before filming and one for during filming.

3D model of the Bell & Howell tripod head. The tripod head made it possible to slide the camera into focusing position.

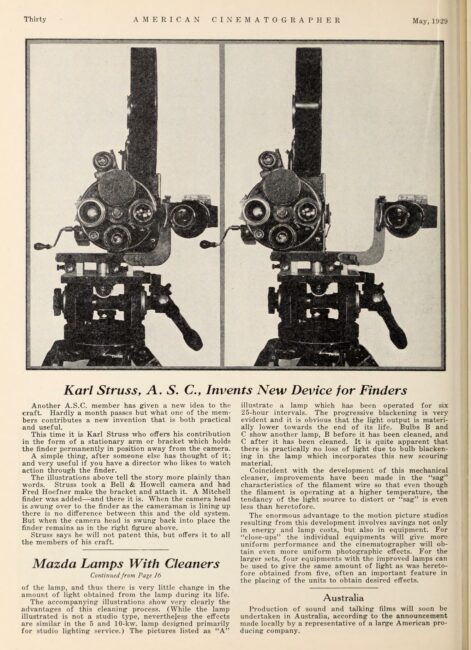

Photograph of an accessory used to attach the viewfinder. The two images illustrate the movement of the camera from its framing/focusing position to its shooting position. Photograph from The American Cinematographer, 1929.

Copyright: Public domain

Framing and focusing were done in four steps:

“Focussing was accomplished by rotating the turret through 180 degrees so that the lens which was to be used in taking the shot was in front of the ground-glass screen on the other side of the camera, where the image on it could be viewed through an eyepiece to the side of the camera. Before this was done the camera was slid sideways on the special baseplate on which it was mounted so that the lens was restored to the position in space that it would occupy when the shot was actually photographed—the two displacements by rotating the lens turret and moving the body cancelling to eliminate the parallax that would otherwise occur. The camera also had a supplementary viewfinder system for use when the shot was actually being taken.” (Salt 2009, 88)

The Bell & Howell had to be cranked at a rate of two revolutions per second (like the Cinématographe). This allowed camera operators to vary the shooting speed to create accelerated effects during projections. This creative freedom was made possible by the crank. Starting in 1919, the crank could be replaced by an optional motor.

Camera operators often rested their wrists on the crank shaft extension. The camera was heavy, and because it was mounted on a tripod, there was no need to immobilize it while filming.

When the tripod was set to its maximum height, the camera storage box could be used as a step stool by the camera operator.

During the actual shoot, camera operators could not see what they were filming. Mastering the movement of the camera “blindly” was difficult and required experience. It should be noted that at that time, cameras were rarely moved, meaning that the camera operator generally remained in place while filming.

Camera operators normally operated the camera alone, but this became more difficult when camera movements were required, since they required that the tripod crank handles be manipulated. Although some camera operators succeeded in doing both, that is, operating the camera with one hand and manipulating the tripod cranks with the other to pan vertically and horizontally, assistants often carried out this task when they were available.

This implies that assistant camera operators were not in charge of the camera itself. In those days, assistants were assigned fairly simple tasks, such as transporting the camera, identifying the shots with the clapperboard, holding reflectors and marking the studio floor to define the limits of the frame for the actors. They also took notes about each shot, such as the length of the shot, the camera settings and the actors’ entrances and exits.

When assistants were asked to move the camera, they had to remain in sync with the camera operator and operate the tripod’s cranks at the speed required for the desired movement.

To make the camera more mobile, large productions would sometimes mount a Bell & Howell onto the back of a vehicle that had been fitted out for the purpose. Another option was to have the set move behind the actors, rather than move the camera.

Photograph of the filming of Ben Hur, 1925. Two camera operators and their Bell & Howell cameras are filming the chariot race from the rear of a converted vehicle. Photograph from the book: Hampton, Benjamin B. 1931. A History of the Movies. New York: Covici-Friede Publishers, p. 560.

Copyright: Public domain

Who used the Bell & Howell?

From the outset, the Bell & Howell Company’s goal was to cater to the growing film industry. Their camera was designed and used by professional camera operators.

To be a competent professional camera operator, certain qualities were required, such as meticulousness, good concentration, strong technical knowledge, manual dexterity, resourcefulness, a well-developed artistic eye and a good memory.

James Wong Howe was a renowned camera operator and cinematographer who worked on over 130 films. He is photographed here with a Bell & Howell on the set of The Alaskan in 1924.

Copyright: Public domain

As the film industry grew, men predominantly held these positions. However, a great many women also operated or made films with this camera in the late 1910s.

Photograph of actress May Allison, on the left with a Bell & Howell, and of Helen Taft, First Lady of the United States from 1909 to 1913, on the right.

Copyright: Public domain

Nell Shipman manipulating film in the camera.

Copyright: RGR Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

3D model of a Bell & Howell operator and assistant.

Additional resources

This motion picture glossary will help you better understand some of the terminology used.

Are you the inquisitive type? Would you like to learn more about the Bell & Howell and the filmmakers who used it? The following websites will provide you with additional information.

- The Balloonatic, co-directed by Buster Keaton and Edward F. Cline in 1923. Filmed with a Bell & Howell 2709. Available in full online.

- The General, co-directed by Buster Keaton and Clyde Bruckman in 1926. Filmed with a Bell & Howell 2709. Available in full online.

- The Extra Girl, directed by F. Richard Jones in 1923, with Mabel Normand in the title role. One scene shows two Bell & Howell 2709 cameras being used on a film set (from 37:33 to 41:31).

- The Gold Rush, directed by Charlie Chaplin in 1925.

- In his book Adventures with G. W. Griffith, published in 1988 by Faber & Faber, Karl Brown provides an enlightening account of the life and apprenticeship of a camera operator of the era.

- Women Film Pioneers Project

- American Society of Cinematographers

- Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938

- Trailer for the documentary film The Women Who Run Hollywood.

Bibliography

Howell, Albert S. 1911. Motion Picture Machine. Patent No. 1,038,586. United States Patent Office.

Mannoni, Laurent. 2016. De Méliès à la 3D : la machine cinéma. Paris: Lienart Éditions.

Morris, Peter. 1978. Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895–1939. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Raimondo-Souto, H. Mario. 2007. Motion Picture Photography: A History, 1891–1960. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland.

Salt, Barry. 2009. Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis. London: Starword.

Shipman, Nell. 1987. The Silent Screen & My Talking Heart. Boise: Boise State University.

Want to find out more?

Take an audio journey into the world of this device.