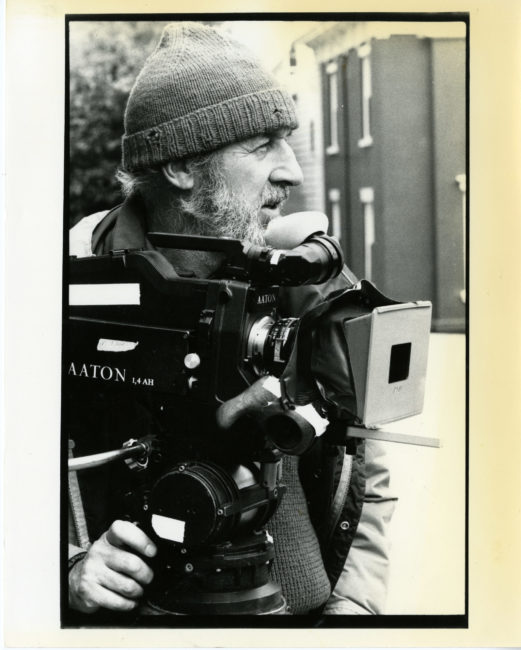

It is not easy to meet the needs of documentary filmmakers, whose objective is to capture people’s authentic realities as they experience them. The Aaton meets these needs. It is the product of research aimed at developing lightweight cameras. Designed to be carried on the operator’s shoulder, it can record sound and image simultaneously, without the need for a cable.

Refer to the “Additional resources” section to see a glossary of technical terms.

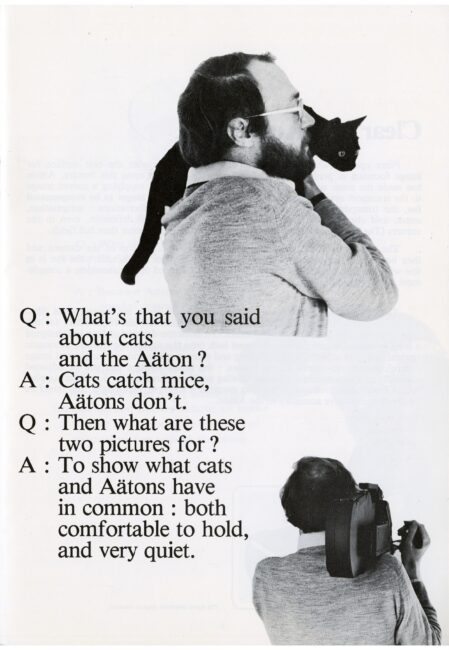

A cat on the shoulder for recording on the go

Of course, the Aaton looks nothing like a cat. Designed to be carried on the shoulder, it allows operators to get close to their subjects. Created in 1972 and still widely used today, the Aaton’s ergonomic design offers comfort and stability.

The Aaton was the product early 1960s research on designing lightweight, synchronous cameras. It became well-known for some of its technological innovations, such as sound-image synchronization, a silent motor, low weight, quick reel changes and a timecode imprinted directly on the film, among others.

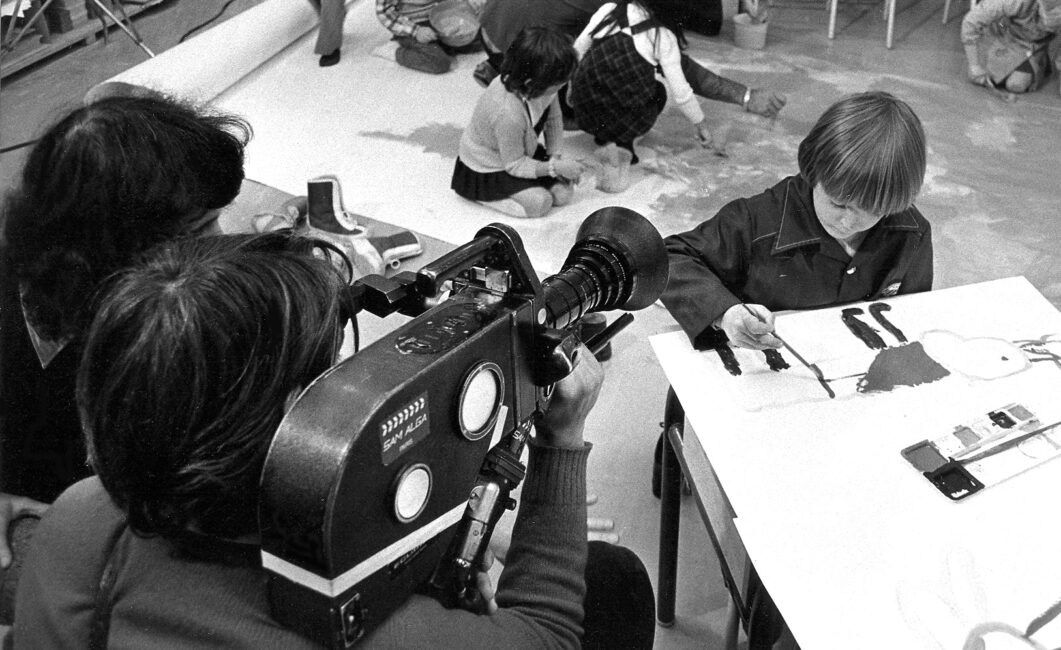

The Aaton represented the next step in 1960s documentary filmmaking: It was lightweight and it synchronized sound with video. Finally, filmmakers could record the candid words and movements of people in their own environments. In small teams, they produced films that were a far cry from the “frozen aesthetics of beautiful documentaries” (Bouchard 2012, 79). These filmmakers avoided predetermined settings, preferring to adapt their approaches to suit a film’s subjects. Natural lighting was favoured, and crew members generally avoided adding their own commentaries.

A few films shot with the Aaton

Many films shot in Quebec, France and the United States were produced thanks to the Aaton and its useful features.

Liberty Street Blues directed by André Gladu in 1988

Narrator : Éric Gaudry

© ONF

A vibrant and colourful portrait of New Orleans: Its musicians young and old, its brass bands, its traditions, its unique culture.

Liberty Street Blues

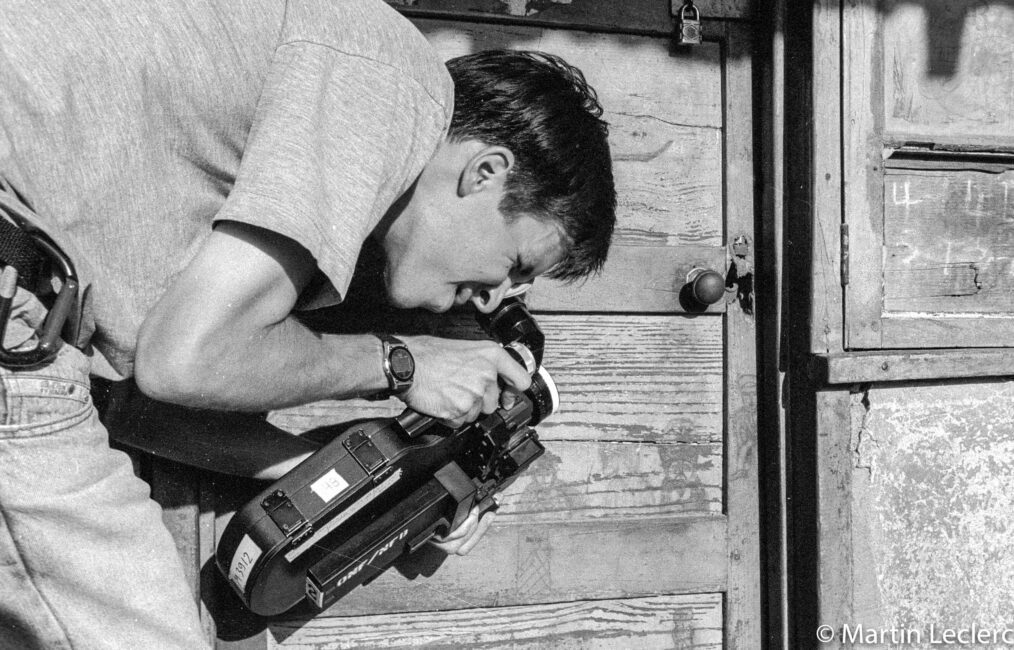

Directed by André Gladu, with Martin Leclerc on camera, Liberty Street Blues is a documentary that channels the philosophy of Direct Cinema. The camera operator’s full immersion in the atmosphere of the parade is a key element of the film. Leclerc, with his Aaton on his shoulder, is very mobile, weaving through the crowd with ease. He moves from inside a bar to outside on the street in one fluid motion. His camera allows him to film his subjects without constraint, while the equally mobile audio operator follows at a comfortable distance. The camera operator is able to film the parade at a human level and circulate amongst the musicians and dancers.

Liberty Street Blues directed by André Gladu in 1988

Narrator : Éric Gaudry

© ONF

A vibrant and colourful portrait of New Orleans: Its musicians young and old, its brass bands, its traditions, its unique culture.

Note: The information in square brackets describes the audio and visual content of the clip. The remainder of the text corresponds to narration and dialogue. The French passages in the video have been freely translated and are written in italics.

[One long take, 0:48 seconds.]

[Inside a bar, daytime. New Orleans, United States. Colour.]

[Jazz music plays in the background.]

[The clip begins inside a bar. A man is playing pool.] [Sound of pool balls colliding with each other.]

[The viewer has the same subjective point of view as the camera operator, who is carrying the camera on his shoulder. The operator advances toward the exit.]

[Continuous sound of a crowd. Conversations and applause can be heard here and there throughout the clip.]

[In a travelling shot, the operator exits the bar and goes out onto the street. At the same time, a man enters the bar and speaks to a woman standing in the doorway.]

They are getting ready to start dear.

[Once outside, the operator begins to walk through the street. As he moves forward, he films the people he encounters. They are crowded together, waiting for the parade to resume. Two men shake hands. A man makes a peace sign at the camera.] [The volume of the music lowers.]

Deux heures et demie. Premier arrêt. Il y a quatre ou cinq temps d’arrêt pendant la parade. Les musiciens se font payer la traite. [2:30 p.m. First stop. There will be four or five breaks during the parade. The musicians are provided with refreshments.]

[The crowd is dense. The atmosphere on the street is one of lively conversation and laughter. People are dressed in regalia, wearing colourful hats and clothing. They pay no attention to the camera, which moves smoothly and easily among them. The sequence continues, showing a musician from the Young Tuxedo group chatting with an older man, who is also participating in the parade. The musician is holding a trombone.]

[Noise of the crowd and the sound of clapping hands, growing louder.]

[Shoulder shot of two young girls, in profile, playing a hand clapping game. After a first round, the girl on the right shouts.]

Foul!

[The girls begin a second round of the clapping game. After bungling a sequence, they stop and look at each other.]

[End of scene.]

Liberty Street Blues directed by André Gladu in 1988

Narrator : Éric Gaudry

© ONF

A vibrant and colourful portrait of New Orleans: Its musicians young and old, its brass bands, its traditions, its unique culture.

Liberty Street Blues

Directed by André Gladu, with Martin Leclerc on camera, Liberty Street Blues is a documentary that channels the philosophy of Direct Cinema. The camera operator’s full immersion in the atmosphere of the parade is a key element of the film. Leclerc, with his Aaton on his shoulder, is very mobile, weaving through the crowd with ease. He moves from inside a bar to outside on the street in one fluid motion. His camera allows him to film his subjects without constraint, while the equally mobile audio operator follows at a comfortable distance. The camera operator is able to film the parade at a human level and circulate amongst the musicians and dancers.

Liberty Street Blues directed by André Gladu in 1988

Narrator : Éric Gaudry

© ONF

A vibrant and colourful portrait of New Orleans: Its musicians young and old, its brass bands, its traditions, its unique culture.

Note: The information in square brackets describes the audio and visual content of the video. There is dialogue in this clip.

[One long take, 0:43 seconds.]

[Outside on the street during a parade, daytime. New Orleans, United States. Colour.]

[Crowded parade atmosphere.] [Wide shot of the dense crowd. People are dressed in full regalia. The musicians hold their instruments and begin playing. The dancers are in front of the musicians and start the parade, moving to the rhythm.]

[A whistle sounds and the musicians begin to play the jazz classic “Bugle Boy March.”]

[The camera operator frames the legs of a dancer wearing white pants. The dancer holds two wreaths of flowers in his hands, which he moves in time with the music. Then, another wide shot of the other dancers, with the musicians in the background.]

[End of scene.]

Le Roi du drum directed by Serge Giguère in 1991

© Les Productions du Rapide-Blanc

A local hero from east-end Montréal—passionate, whole and naive—Guy Nadon is rhythm incarnate. He is a jazz drummer who can find the beat in anything that makes noise. As the king of musical improvisation—and also a king of theatrical improvisation—he sometimes makes comments that border on the surreal. He is a do-it-yourselfer who makes his own drum kits and creates his own universe whenever he’s behind them. It’s an unbridled universe, a reflection of Montréal in the 1950s…its nightclubs…the golden age of jazz in Quebec. (Rapide-Blanc Productions) / At first glance, it’s a fresco of unrestrained passion, but it’s also the disjointed, social and historical portrait of a regular guy from east-end Montréal—Guy Nadon—who went from banging on tin cans to becoming a unique drumming phenomenon. And beyond the phenomenon, it’s also the poetry of his persona. (Annuaire du cinéma québécois, 1991)

Le Roi du drum

Produced and filmed by Serge Giguère, Le Roi du drum highlights the importance of the relationships between camera operators and their subjects. To be able to film Guy Nadon and Vic Vogel so naturally in their own environment—indoors and in a relatively confined space—the camera operator first had to build a relationship of trust with his subjects. This relationship created a playful atmosphere in which authentic moments coexist harmoniously with pure fiction. It also allowed percussionist Nadon to let his remarkable talent shine through.

Le Roi du drum directed by Serge Giguère in 1991

© Les Productions du Rapide-Blanc

A local hero from east-end Montréal—passionate, whole and naive—Guy Nadon is rhythm incarnate. He is a jazz drummer who can find the beat in anything that makes noise. As the king of musical improvisation—and also a king of theatrical improvisation—he sometimes makes comments that border on the surreal. He is a do-it-yourselfer who makes his own drum kits and creates his own universe whenever he’s behind them. It’s an unbridled universe, a reflection of Montréal in the 1950s…its nightclubs…the golden age of jazz in Quebec. (Rapide-Blanc Productions) / At first glance, it’s a fresco of unrestrained passion, but it’s also the disjointed, social and historical portrait of a regular guy from east-end Montréal—Guy Nadon—who went from banging on tin cans to becoming a unique drumming phenomenon. And beyond the phenomenon, it’s also the poetry of his persona. (Annuaire du cinéma québécois, 1991)

Note: The information in square brackets describes the audio and visual content of the clip. The remainder of the text corresponds to dialogue. The French passages in the video have been freely translated and are written in italics.

[1:34 minute sequence.]

[Inside a house, daytime. Colour.]

[The sequence has two male protagonists: Guy Nadon, the King of Drums, wearing a floral shirt and thick eyeglasses, and Vic Vogel, sporting a goatee and wearing a souvenir t-shirt from Florida.]

[Medium close-up of Vogel, sitting on a piano bench in front of a piano. The walls behind him are covered in very large abstract works of art. He is facing the camera, head slightly turned to the left of the frame. He addresses Nadon, who is off screen.]

Vogel: Dis donc, te rappelles-tu pourquoi que t’as joué une fois avec tes criss de souliers ? T’rappelles-tu ? [Tell me, do you remember why you played with your freakin’ shoes that time? Do you remember?]

[Nadon, sitting on a stool in front of his drum kit, facing the camera, responds to Vogel, who is now off-camera, just behind the camera operator. Nadon leans forward, and then, in the middle of his sentence, raises his arm to emphasize his point.]

Nadon: C’est pour capter l’attention des gens. C’est pour faire un show, un showbizz. [It was to grab people’s attention. It was to put on a show, a spectacle.]

Vogel: Tu vas dire… Toé… Tu voulais être accepté ? [You mean… You… You wanted to be accepted?]

[Zoom in for a close-up of Nadon’s face. He leans forward to clearly grasp Vogel’s words.]

Nadon: Accepté ! [Accepted!]

Vogel: Par le, la foule ? [By the crowd?]

Nadon: [With hand gestures] Ouais, accepté par la foule, pour pas passer dans l’ombrage. [Yeah, to be accepted by the crowd, and not just be part of the scenery.]

Vogel: Yeah, yeah, you wanted to be somebody!

Nadon: [Nodding] Somebody.

Vogel: You wanted to be in show business!

Nadon: [Nodding] Show business.

Vogel: Right!

Nadon: [Smiling] You never, uh, y’est jamais trop tard pour être dans le showbizz ! [it’s never too late to get into show business!]

Vogel: Bin même l’Orchestre symphonique c’est le plus grand showbusiness au monde [Well, even the Symphony Orchestra is some of the biggest show business in the world.]

Nadon: Oui. [Yes.]

Vogel: Ti-Guy, est-ce que t’es encore capable de faire ça ? [So, Guy, are you still able to do it?]

Nadon: [Nodding] Totalement monsieur Vogel ! [Totally, Mr. Vogel!]

[Music is heard until the end of the clip: A piano and drum duet.]

[A completely black screen, with only a few discernible fluorescent elements: drumsticks, the outline of a drum, a lapel pin and Nadon’s eyeglasses. These are the only items that can be seen on the screen. Nadon plays the drum, and the drumsticks move up and down at high speed.]

[Back inside the house. Nadon, medium close-up, sitting at his drums. He plays the drums, using slippers as drumsticks. He strikes the various drums and cymbals on his drum kit at high speed with a big smile, leaning from side to side to use every part of his instrument. He even taps the slippers together to create new sounds. Off-screen, Vogel accompanies him on the piano.]

[Back to the black screen. Close-up of Nadon’s eyeglasses, then of his drum, and lastly of one of his drumsticks, which he spins in his hand like a propeller.]

[Back to a close-up of the slippers used by Nadon, then zoom out to re-frame the top half of Nadon’s body and the entire drum kit. The camera moves slightly to the left and then turns to film Vogel, who is at the piano, in profile. Their musical number ends with a few notes of the piano, and then Vogel raises his arms in the air.]

[End of scene.]

The origins of a camera: Quintessential portability for professionals

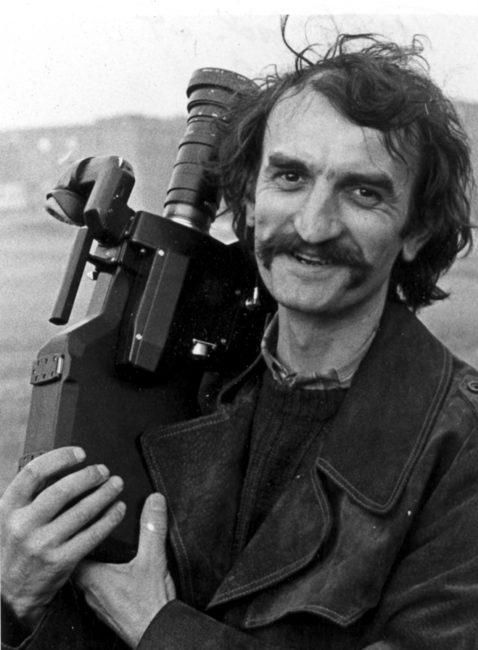

The quest for a portable camera led engineer and movie buff Jean-Pierre Beauviala to create a professional camera that would meet his own needs.

As he set out to create a film experience that would provide viewers with an immersive audiovisual experience in the streets of Grenoble, France, Beauviala came to realize there were no cameras available that could synchronize sound and image without being restrictive. Like many filmmakers of the ‘50s and ‘60s, Beauviala was confronted with a lack of suitable equipment for capturing live, immersive shots.

Photograph of Jean-Pierre Beauviala in 1972.

Jean-Pierre Beauviala – CC BY-SA 4.0

Beauviala initially worked for one of France’s largest camera manufacturing companies, called Éclair. His experience as a consulting engineer, and later as a director of studies, trained him in the design of filmmaking equipment. The Aaton was directly descended from two iconic Éclair cameras widely used by Direct Cinema and New Wave filmmakers: The Éclair 16 and the Caméflex. For example, the Éclair, like the Aaton, was carried on the shoulder, but it was too front-heavy, forcing users to either overcompensate for its instability or wear a harness, both of which caused physical discomfort after several hours of shooting. In addition, there were synchronization issues between the image and the sound that had to be remedied through the use of cables.

Coutant, Clément and Jacques Mathot. 1961. Brevet d’invention [Patent of invention]. No. 1318665. Paris, France. 3 p.

Public domain

Patent of invention of the Éclair camera

This three-page patent contains two pages of written descriptions, with a full-page image of the proposed camera on the last page. The patent protects the intellectual property of the inventors and guarantees the inventors’ exclusive rights to the patented invention.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Coutant, Clément and Jacques Mathot. 1961. Brevet d’invention [Patent of invention]. No. 1318665. Paris, France. 3 p.

Public domain

To make modern cinematic cameras more silent, it is customary to place them in soundproof blimp housing with optical glass at the front and portholes at the back and on the sides, these portholes being intended to permit visual access to the camera’s various dials and controls.

Unfortunately, soundproof casing is always heavy and cumbersome and, moreover, the optical glass placed in front of the lens can distort the recorded image. The possibility of doing away with cumbersome soundproof casing entirely and rendering cameras more silent through highly precise mechanical processes was also considered; however, the results were never adequate, due to the high sensitivity of the modern microphones used in audio recording.

In a camera, one of the loudest noises is generated by gears located between the camera’s motor and its rotating reflex shutter, commonly called the Reflex viewfinder.

The object of the present invention is a camera that is made particularly quiet by the fact that its motor drives the rotating reflex shutter directly, without any intervening gears.

Another feature of this invention is that the motor that drives the shutter is located underneath the camera, so that it rests forward of the operator’s shoulder, while the magazine at the back of the camera rests on top of the operator’s shoulder, thus ensuring that the camera is properly balanced while recording.

The attached drawing shows a diagram of the present invention.

The camera (1) is equipped with, in the usual manner, a magazine (2) at the rear, and the film (3) scrolls behind the lenses (4) and (5); between the film (3) and the lenses (4) and (5) is the rotating reflex shutter (6), which is direct driven by the motor (7), which itself is insulated by rubber (8) inside a housing (9) and which triggers the reflex shutter via rubber discs (10); in the conventional manner, the viewing device is constituted of the magnifier (11), the taking lens (12), the reflective surface (13) and the ground glass (14), upon which an image identical to that on the film (3) is formed.

It is conceivable that with this type of camera, not only will the desired result be achieved, i.e. a considerable reduction in noise due to the total elimination of gears, but the device will be particularly useful because the motor’s housing can be placed against the operator’s shoulder while the magazine rests upon it.

It is understood that the embodiment of the invention described above with reference to the attached drawing is purely indicative and in no way restrictive, and that numerous modifications may be made without departing from the scope of the present invention. [Translation]

Photograph of a camera operator with an Éclair on his shoulder. The bulk of the camera’s weight sits forward of his shoulder. The Aaton’s design is similar to this one.

Podzo Di Borgo CC BY-SA 4.0

Beauviala invented different cameras to overcome these problems, as well as to satisfy a desire for formal and aesthetic renewal that was shared by 1960s filmmakers from Quebec, France and the USA.

The Aaton company was formed in France in 1971 by Jean-Pierre Beauviala. He and his team never stopped perfecting their cameras in an effort to attain their ideal:

Beauviala’s main goal continues to be to design what he calls ‘a friendlier instrument.’ His primary objective is to develop a tool that corresponds to his vision of an ideal movie camera—a ‘cat-on-the-shoulder.’ This guiding principle serves as the basis—constantly renewed and re-examined—of the development of a whole range of 16 mm cameras. Their varying technical characteristics all derive, either directly or indirectly, from the primary goal of making a camera into a ‘cat’. [Translation]

(Grizet 2017, 39).

Excerpt from an Aaton cameras brochure.

Anon. 1978. Aaton Cameras. p. 5.

© Aaton Digital

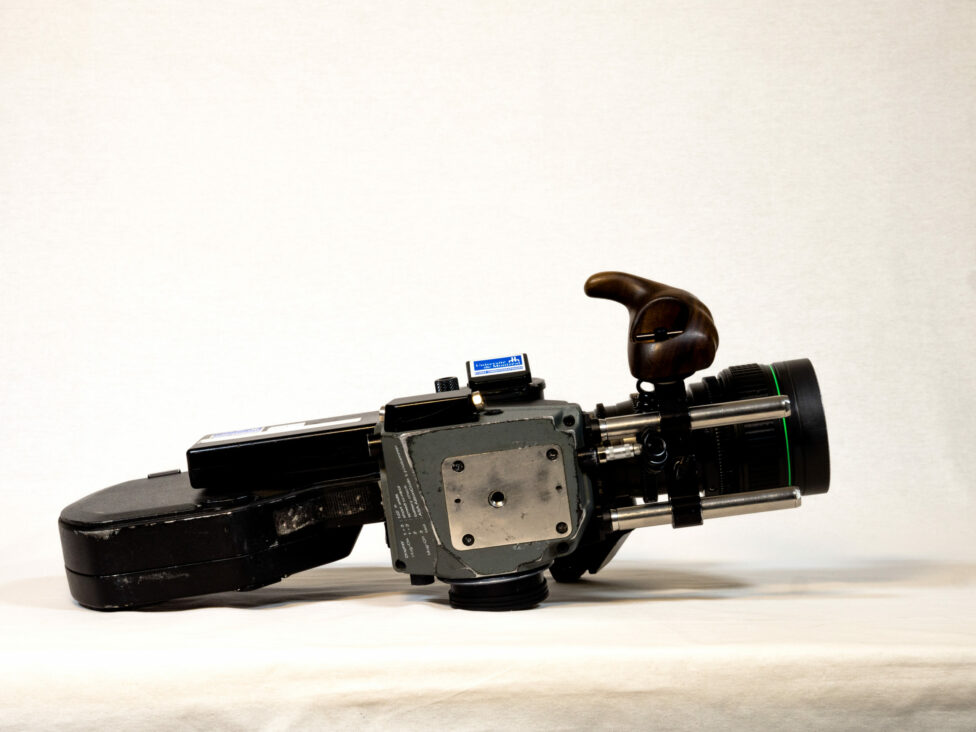

After two years of research and testing, the company’s first camera, the Aaton 7, was launched in 1975. It allowed the image to be synchronized with the sound recording without the use of cables, thanks to its “universal quartz-controlled motor.” The properties of quartz had already been adopted by watchmakers for their precise timekeeping. In the Aaton camera, they allowed the speeds of the two devices’ motors (the camera’s and sound recorder’s) to be precisely aligned.

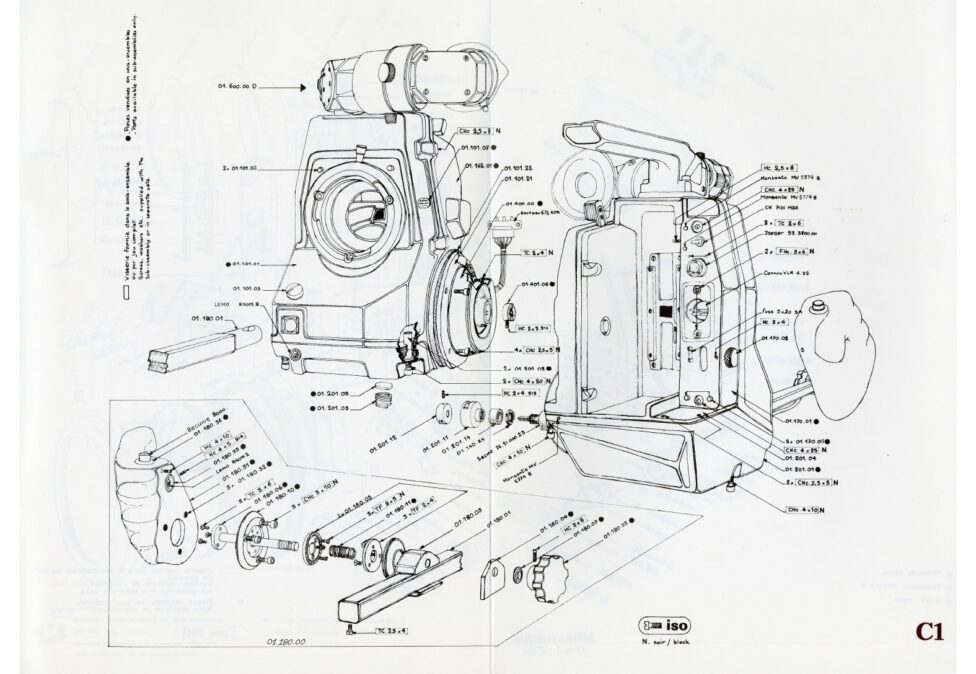

Aaton technical data sheet

Which characteristics of this device make it so portable and lightweight and allow it to approach its subjects?

Specifications

- Measurements

- 50 cm x 20 cm x 23 cm.

- Weight

- 6 kg, including batteries and magazines.

- Materials

- The camera is made up of electronic components that perfectly synchronize the image with the sound recording.

- Frame rate

- Variable frame rate of 6 to 32 fps.

Components and accessories

- Battery

- Under normal conditions, the battery can power the camera through up to five magazines of film.

- 16 mm film

- This highly light-sensitive film allows operators to shoot in all types of conditions, both indoors and outdoors, as well as at night.

- 120-metre magazine

- The preloaded magazines can be installed and removed quickly, which is very advantageous when shooting on the go.

- High-performance reflex viewfinder

- It offers precision frame control, as the operator can see exactly what is being filmed at the time of shooting.

- AatonCode

- This camera was one of the first to directly embed a time code onto the film when shooting. This allows the sound and the image to be synchronized.

- Walnut wood grip in the form of a closed fist

- Adjustable to fit the camera operator’s hand. It allows for easier camera handling.

Features

- No integrated microphone. An external microphone is required.

- The microphone is mounted onto a boom that is operated by the sound mixer. The sound mixer, who works independently from the camera operator, can record freely at a distance from the camera.

- Zoom lens.

- Used by documentary filmmakers, the zoom lens provides great flexibility without lens changes, and thus without shooting interruptions. It can be used for zoom-in and zoom-out effects.

- Very silent.

- The very quiet camera motor produces approximately 23 decibels of sound, equal to a barely audible whisper.

- Cutaway on the body of the camera.

- It allows the camera to be placed on the shoulder, providing it with great stability.

Operation and handling

More than anything, the Aaton fills a need to capture action shots.

Anon. 1981. Aaton Cameras 7 LTR 16 mm Camera Instruction Manual. 29 p. TR 880 A22

© Aaton Digital

Aaton 7LTR 16 mm Camera Instruction Manual.

This 29-page instruction manual provides details on how to set up the camera, operate it and keep it clean. It also explains the acronym LTR. Option ‘L’ designates the integrated exposure meter (light meter), which indicates—through the viewfinder—the amount of light reflected by the subject. This allows the exposure to be adjusted without the use of additional equipment (such as an external light meter). The ‘T’ refers to the easily readable time stamp embedded directly on the film. It makes it possible to reduce the use of clapperboards, which cause interruptions to shooting sequences. The ‘R’ corresponds to the video relay. A small video camera (the Aaton VR30, also called the Paluche) is fitted into the analog camera. It transmits an image of what is being filmed onto magnetic tape, which can be viewed on an external monitor, either by those being filmed, who therefore have better control over their own images, or by the producers controlling the quality of the shoot.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Anon. 1981. Aaton Cameras 7 LTR 16 mm Camera Instruction Manual. 29 p. TR 880 A22

© Aaton Digital

Selected excerpts:

Option L: Exposure Meter

Two photocells measure the quantity of light reflected by the film during the entire exposure time, thus giving a measurement independent of fps.

In test position, one frame is exposed for ¼ of a second; the measurement is corrected to

give an indication usable only at 24 or 25 fps crystal speed (p. 17).

These readings are made looking through the viewfinder in normal use.

When the light level is too low, the green LED on the left is out; when the light level is too high, the green LED on the right is out. Underexposure or overexposure are thus shown even when the darkened diode has gone off the display (p. 18).

Option T: Clear Time Recording

For Clear Time Recording on 16 mm film; the Aaton 7 LTR is equipped with Option T.

This is the actual marking system inside the camera itself: microprocessor circuitry, and fiber optic device to expose clear figures onto the edge of the film each second as it moves over the gate (p. 20).

Option R: Video Relay

Option R consists of two optical subassemblies fitted into the camera body: a beam splitter which bleeds off 35% of the light going from the viewing screen to the viewfinder, towards a relay lens and mirror providing an aerial image of the viewing screen at the rear of the central chassis. To put the R option to work, a small tubular video camera (Aaton VR30) is fitted into the PBX battery/video holder, transforming the aerial image into an electronic signal to be monitored or recorded for later viewing (p. 21).

First, the camera is prepared by the camera operator (or assistant): the film is loaded and the battery is installed. Next, the camera is lifted onto the shoulder and the eye is placed against the viewfinder to frame the shot (the other eye may also provide information on the surroundings, as needed). The hand that is placed on the wooden grip guides the camera, while the other hand adjusts the focal length and/or focuses the image.

The Aaton is comfortable to hold and very stable, as all of its weight is supported by the entire body, not only by the arms. The Aaton is not so much an extension of the camera operator’s body as it is a second, symbiotic entity. The filmmaker and the camera work together to get as close as possible to their subjects. Those who wish to become professional camera operators must train themselves to keep control of the camera while also moving around. It is recommended that they practice a sport to develop accuracy, such as archery, or an activity to help them learn to move fluidly, such as dance, yoga or Tai Chi.

To establish a relationship of trust between the film crew and those whose private lives are being recorded, a film shoot must be prepared in advance. It is relatively easy for small crews of two or three people to be accepted and get close to those being filmed.

The sound mixer and the sound equipment must always be close to the action. The assistant camera operator oversees the mechanical aspects of the camera. This is a more important role than that of assistant camera operators of the early days of cinema (see the Bell & Howell info sheet). This allows the camera operator to focus entirely on what is being shot, while maintaining a close relationship of trust with the subjects. The film crew must become emotionally involved in the action, in order to react quickly and capture significant moments, which are sometimes fleeting.

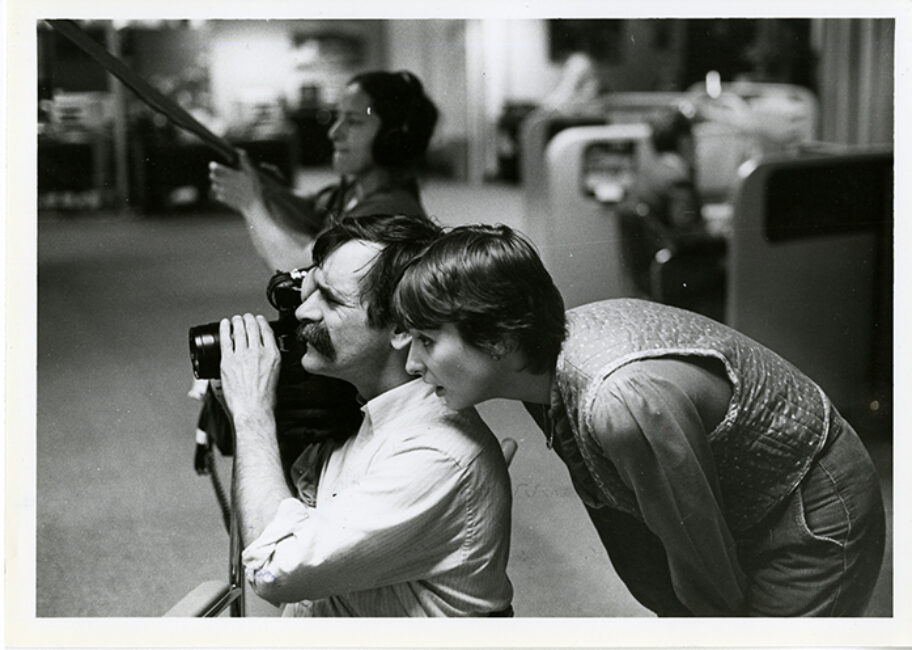

Photograph of director Sophie Bissonnette, camera operator Serge Giguère and boom operator Diane Carrière filming a scene from Quel numéro What number? Photograph by François Bouchard.

Personal collection of Sophie Bissonnette.

Modélisation 3D de l’opérateur de la Aaton, l’assistant-caméraman et le perchiste. L’assistant-caméraman sécurise l’opérateur dans ses déplacements.

Anon. 1978. Aaton Cameras. 47 p. TR880 A222.

© Aaton Digital

1978 Aaton Cameras brochure

This brochure contains descriptions of several Aaton camera models. It features several sections on the LTR. The brochure includes photos from film shoots, advertisements and exploded views of the cameras.

This PDF module may not be accessible. An alternative version is available below.

Anon. 1978. Aaton Cameras. 47 p. TR880 A222.

© Aaton Digital

Selected excerpts:

Cat on the Shoulder

In terms of image sharpness, it is a known fact that film cameras, be they 16 or 35 mm, have a distinct advantage over video cameras. The balance also weighs in favour of film cameras when it comes to freedom of movement and independence. The Aaton L TR goes a step farther with clear marking: assuring absolute sync to the sound recordist even if he is out of sight. To turn these advantages of film to account, however, the camera must be easy to hold, comfortable – in short it has to fit. That is why the Aaton has its characteristic overall shape with a good chunk cut out for the cameraman’s shoulder. And the viewfinder is placed so as to allow easy viewing without fatigue. A logical extension of the ergonomic design is the walnut front handgrip; it slides along a rod right back up against the camera body, enabling the cameraman to lift the camera off his shoulder, and hold it against his head for smooth pan and travelling shots.

Cats don’t bark.

The Aaton was designed to be quiet. It is driven by a brushless motor directly linked to the claw movement; power transmission is by high technology gears – no noisy belts. As the film is flat and smooth while it moves over the aperture plate, it doesn’t need strong rear pressure to hold it in place. This means the claw can move in and out of the perfs under low acceleration; there is no consequent generation of

noise during pull-down. Rarely is the noise level of an Aaton over 28 dB. With special machining (i.e.

more time and more money) it can be made to run at 23 dB; every Aaton has this potential.

Goodbye cables, fatigue, and noise. The cat came back and I’m glad. (p. 4)

Users and anecdotes

In Quebec in the 1950s, NFB productions were made by technical crews that, until then, adhered to relatively rigid standards. Michel Brault, a well-known Quebec cinematographer, cameraman and film producer who was a leading figure of Direct Cinema, described the NFB’s training program: The director of the NFB camera department taught new recruits that in order to produce beautiful images, they had to sit still and examine the frame before shooting. In addition, to synchronize the sound with the image, the words had to be synchronized one by one with the movement of the person’s lips during the editing stage, which was a long and tedious process. An alternative option was to connect the whole system to a power supply, which meant shooting in a studio.

In the mid-1950s, a new generation of francophone filmmakers challenged these codes in their quest for greater authenticity. It was the dawn of Direct Cinema. All that remained to be done was to develop equipment that could meet their needs.

Brault, who was the Aaton brand representative in Canada, explained the importance of the camera in the 1980s.

We were tired of having to shoot documentaries and fiction films with huge cameras that had to be plugged into the 110-volt grid to sync with Hydro-Québec’s 60 Hz cycle. We wanted to be able to go anywhere, without wires getting in the way […] Nowadays, the Aaton is the star. It’s almost perfect. The most ergonomic camera in the history of cinema.

(Brault 1991, 22)

Michel Brault at a shoot. Cinémathèque québécoise collection. Fonds Michel Brault 2019.0084.PH

The Aaton contributed to the tail end of a shift in documentary filmmaking. Both the new role of camera operators and the facility of recording synchronized sound allowed subjects to express themselves without the need for narrated commentary by producers. They could tell their own stories.

Denis Villeneuve uses an Aaton during the shoot of REW-FFW (NFB 1994) in Jamaica.

©Martin Leclerc, photographe

When Beauviala first designed his camera, he had a specific purpose in mind. In practice, the camera was also used for TV reporting. The ORTF (France’s public television station until 1974) was one of the first broadcasters to buy the Aaton. The BBC soon followed. It was also used on major movie sets until the advent of digital cameras.

Additional resources

This motion picture glossary will help you better understand some of the terminology used.

Are you the inquisitive type? Would you like to learn more about Aaton and the filmmakers who used it? The following websites will provide you with additional information.

- A film about Jean-Pierre Beauviala and the Aaton, available online. Un chat sur l’épaule, 2013, directed by Julie Conte. (French with English subtitles)

- Interview with Jean-Pierre Beauviala and Philippe Vandendriessche at the Cinémathèque française in 2014. (French only)

- Interview with Jean-Pierre Beauviala, inventor of the Aaton, on France culture. (French only)

- Quel numéro What number ? Directed by Sophie Bissonnette in 1985. Full version available online.

- Interview with Michel Brault in 1961 on his views of Direct Cinema, also called cinéma-vérité [truth cinema]. (French only)

- Copie Zéro no.5 about Michel Brault’s work. (French only)

Bibliography

Anon. 1978. Aaton Cameras. TR880 A222. Cinémathèque Québécoise collection. 47 p.

Anon. 1981. Aaton Cameras 7 LTR 16 mm Camera Instruction Manual. TR 880 A22. Cinémathèque Québécoise collection. 29 pages.

Bouchard, Vincent. 2012. Pour un cinéma léger et synchrone! Invention d’un dispositif à l’Office national du film à Montréal. Paris: Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

Brault, Michel. 1991. “Métamorphose d’une caméra : fragment d’une langue histoire.” Lumières, no. 25: 22-23.

Coutant, Clément and Jacques Mathot. 1961. Brevet d’invention. No. 1.318.665. Paris, France. 3 pages.

Graff, Séverine. 2014. Le cinéma-vérité: films et controverses. Rennes : Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Grizet, Denis. 2017. “Les appareils de prise de vues de la société Aaton (1971-2013). Du ‘direct’ au ‘numérique’ : enjeux techniques et esthétiques.” Master’s dissertation. Université de Rennes.

Marsolais, Gilles. 1997. L’aventure du cinéma direct revisitée. Laval: 400 coups.

Mouëllic, Gilles (dir.). 2020. “L’innovation technique, de l’argentique au numérique : le cas de la société Aaton.” Encyclopédie raisonnée des techniques du cinéma. Under the direction of André Gaudreault, Laurent Le Forestier and Gilles Mouëllic.

Mouëllic, Gilles, et Giusi Pisano (dir.). 2021. Cahier Louis-Lumière, n° 14 (issue “Aaton: le cinéma réinventé.”).

Sorrel, Vincent. 2017. “L’invention de la caméra Éclair 16 : du direct au synchrone.” 1895, n. 82: 106-131.

Want to find out more?

Take an audio journey into the world of this device.